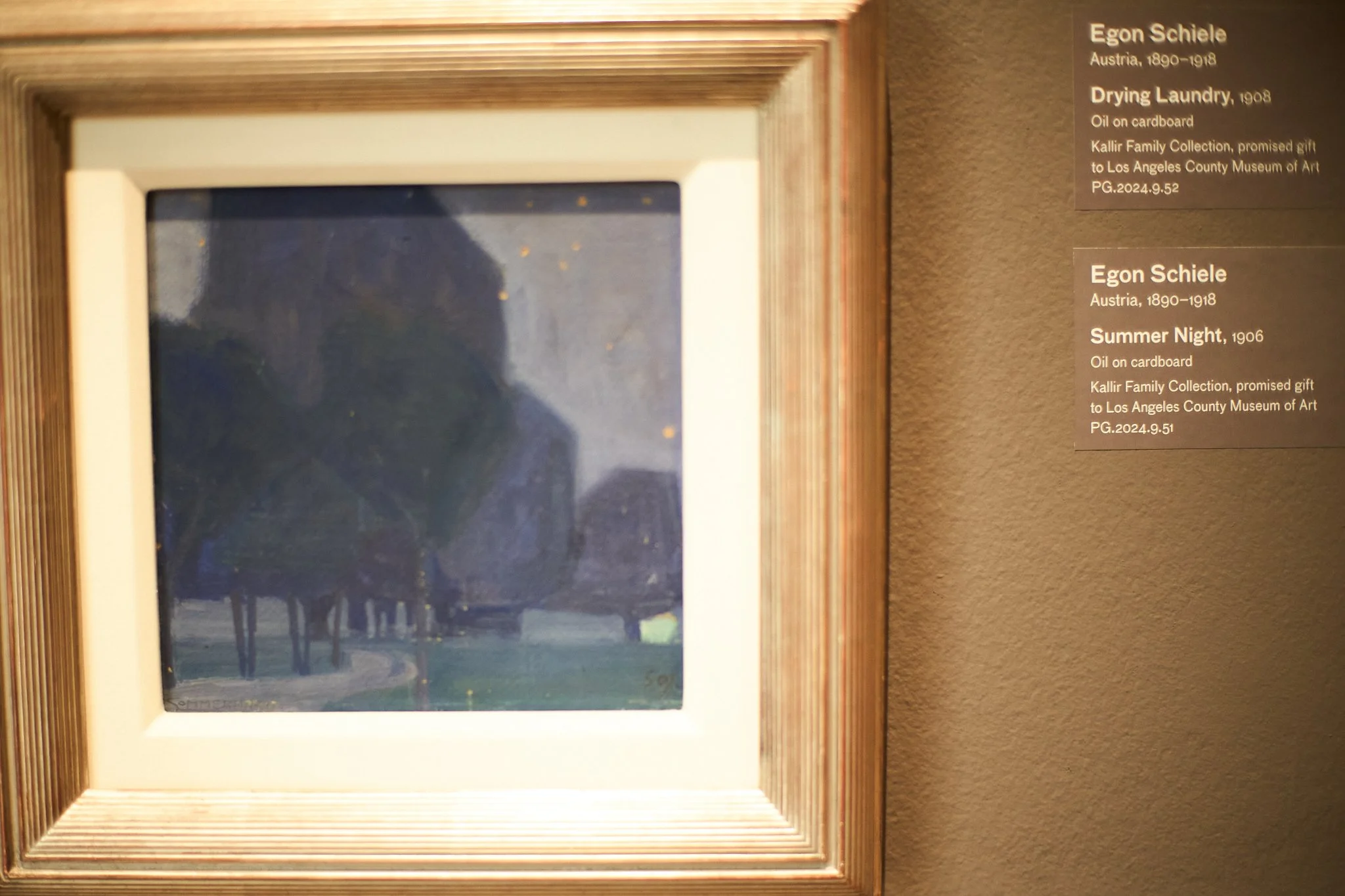

Austrian Expressionism and Otto Kallir

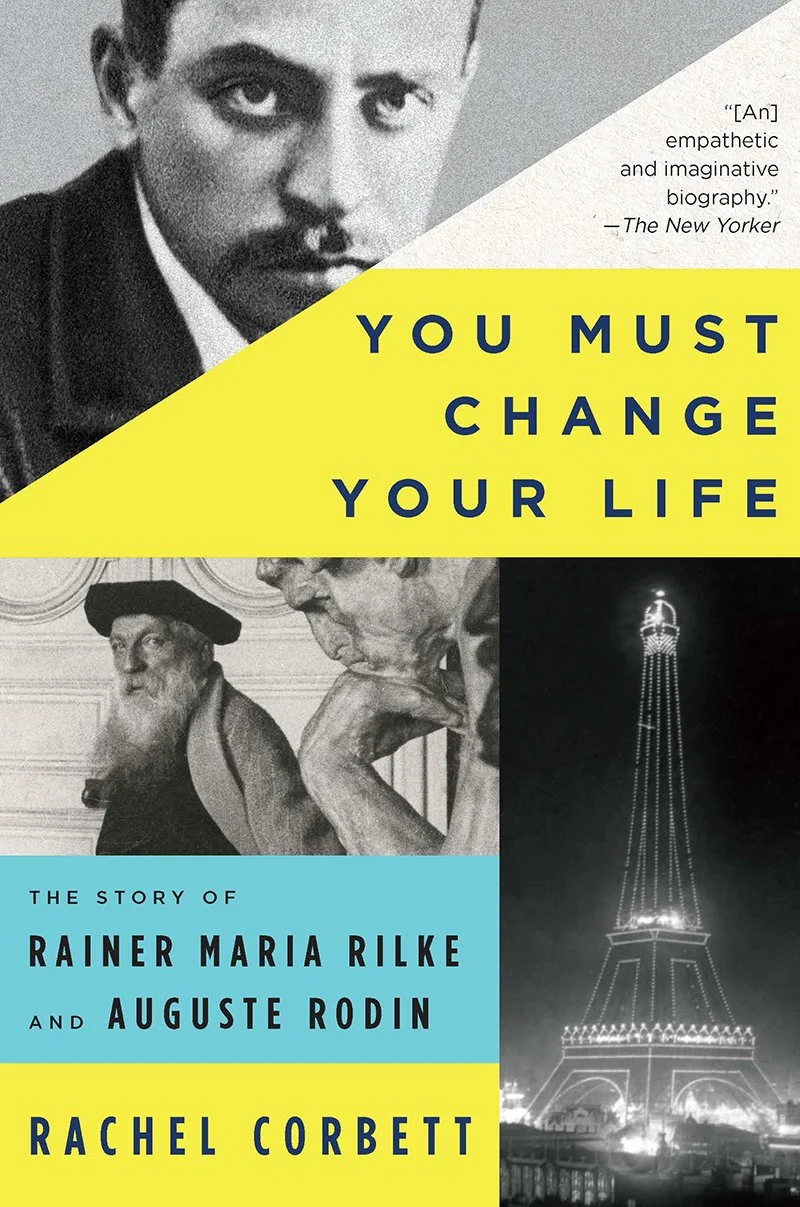

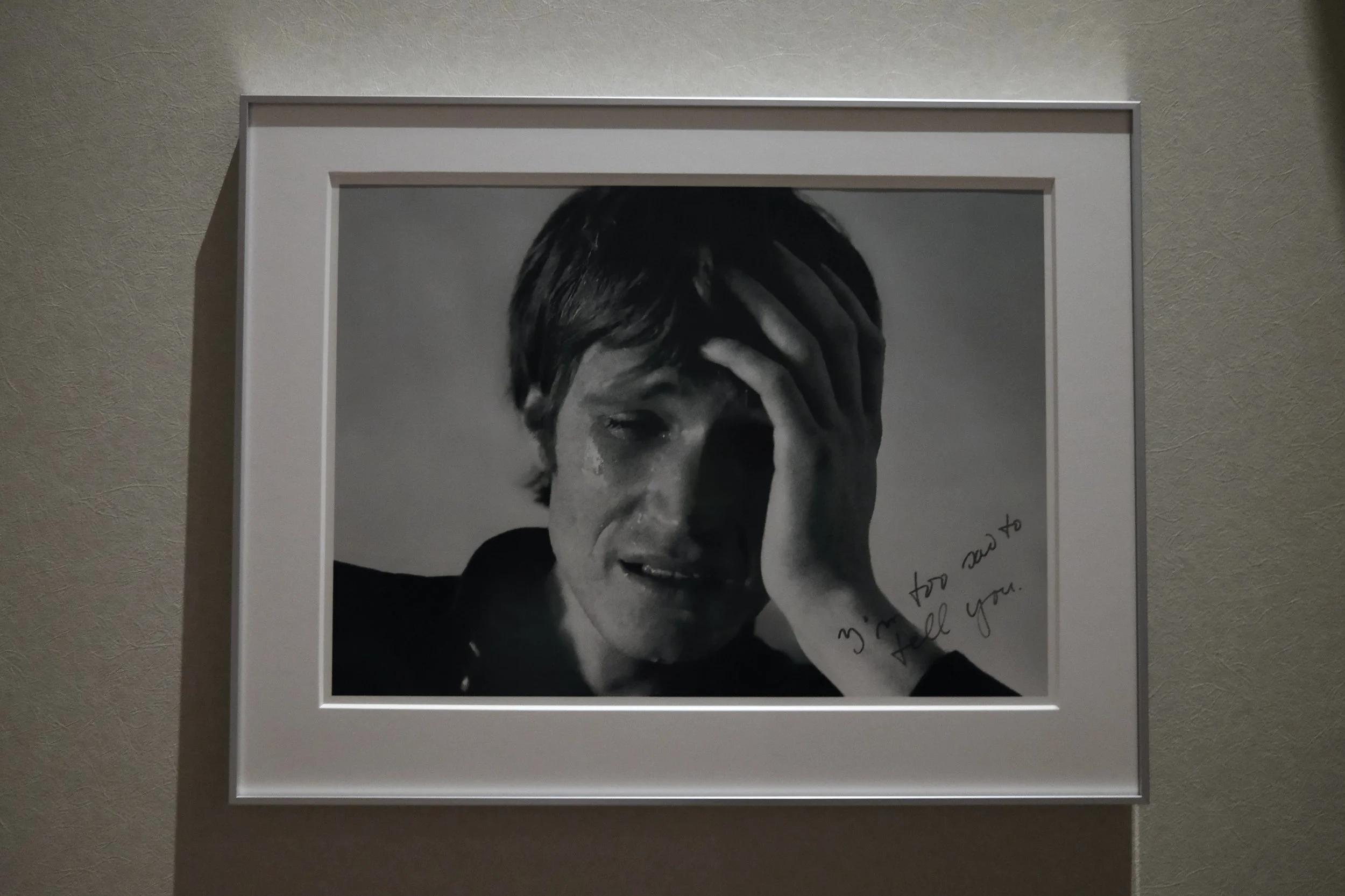

YOU MUST CHANGE YOUR LIFE - Rachel Corbett

AFTER JUST TEN DAYS with Rodin, Rilke sent his new master a letter. He confessed that it might seem strange to write since they saw each other so often, but he felt the language barrier prevented him from fully expressing himself. In the quiet of his little room he could work out the words to tell Rodin precisely how much he had inspired him. He had given him the strength to suffer through loneliness, to accept sacrifice and to "disarm even the anxieties of poverty." He told him that his wife had agreed with him on this, and would be joining him in Paris soon. If they could both find work there, they hoped to stay indefinitely. He sensed that this journey would prove "the great rebirth of my life."

You must change your life, Rachel Corbett page 90

Rodin did not await inspiration, for some pure expression to flov from his soul onto passive materials, as Rilke had always done. To Rodin, god was "too great to send us direct inspiration." Instead, it was up to the artist to create "earthly angels." That's why Rodin approached unformed clay "without knowing what exactly would result, like a worm working its way from point to point in the dark, Rilke would write in the monograph. He would grab hold of it with his huge hands, work it over, spit on it and come to know it entirely, energizing the object and stirring it to life in the process. "The creative artist has no right to select. His work must be imbued with a spirit of unyielding dutifulness," Rilke wrote.

Rodin's hyper-animated style of sculpting produced no less dynamic bodies of work. Rodin manipulated light to enhance the sense of movement in his figures. When the geometry of the planes aligned just right, light would coast and dart across the surfaces and create the illusion of motion. Sometimes Rodin measured the success of this effect by employing a candle test, which illuminated the points of intersection between light and shadow. Rodin once demonstrated the test to a student at the Louvre. Arriving in the evening, just before the museum closed, he held up a candle to the Venus de Milo. He instructed the student to watch the light as he moved it around her contours. Notice how it glided across over the surfaces without jumping at a single hollow, rift or seam. Candlelight revealed all flaws, he believed.

You must change your life, Rachel Corbett page 92

Each day after the library closed, the poet walked back toward his hostel along the Seine, pausing at the ile de la Cité to watch the sun set over the two towers of Notre Dame. The cathedral built for the Virgin Mary had been ravaged and restored in battle after battle, its ornaments were looted, yet its walls stood as strong as its namesake's will was chaste. To Rilke, it was all the more beautiful for enduring that humiliation. This was the hour when the river turned to "gray silk" and the city lights glowed like stars fallen from the sky. Once darkness fell, people would once again pollute the air with their music and perfume, but cathedrals always offered asylum from the senses. Like a forest or an ocean, a cathedral was a place where the world hushed up and time stood still.

You must change your life, Rachel Corbett page 93

Rodin's mantra, Travailler, toujours travailler, contradicted everything Rilke had learned about the fusion of art and life in Worpswede. But the poet had spent years watching the clouds, anxiously awaiting a muse that never came. Rodin's example gave him permission to act. Now, to work was to live without waiting. More than that, Rilke con-cluded, "to work is to live without dying."

You must change your life, Rachel Corbett page 93,94

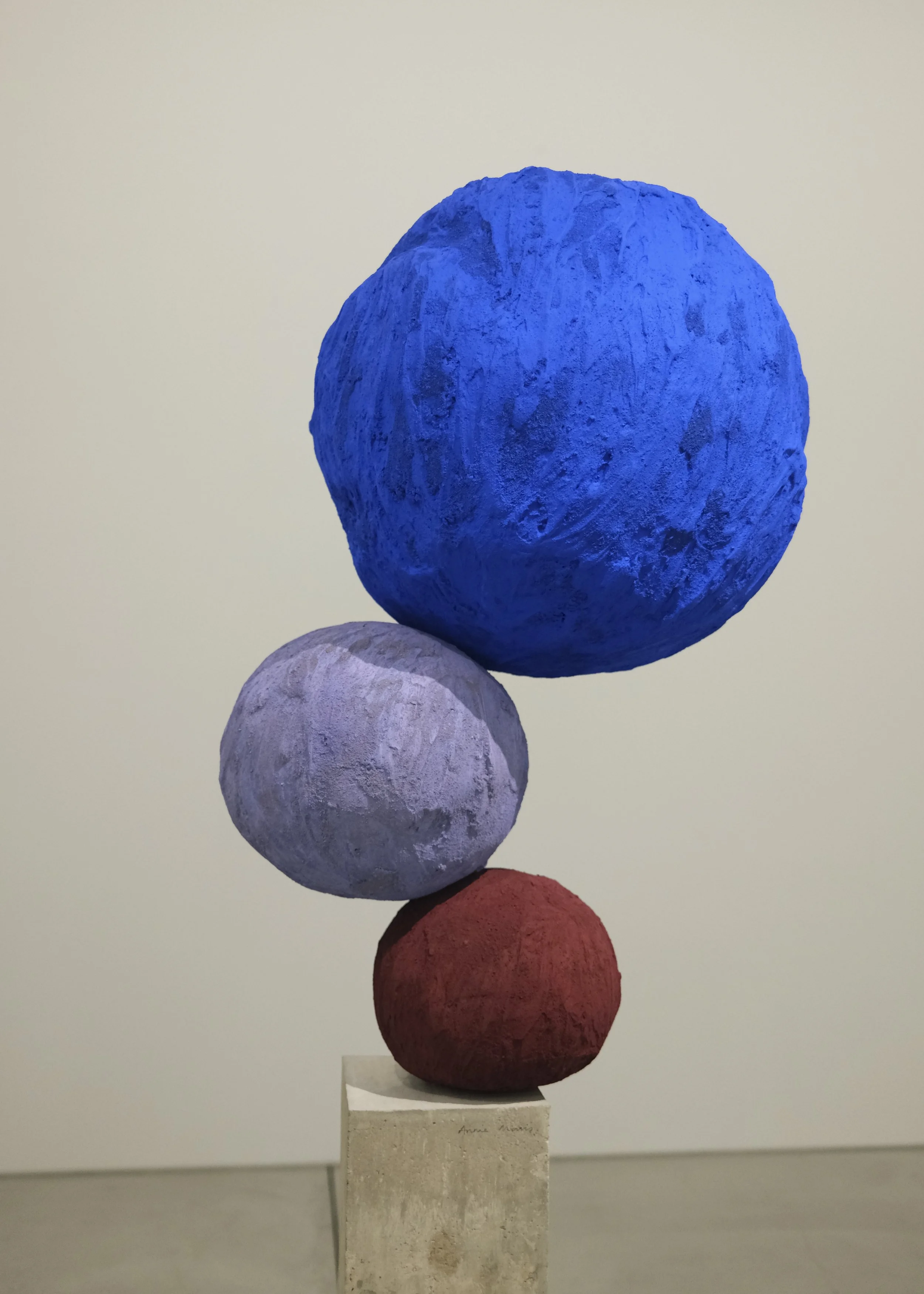

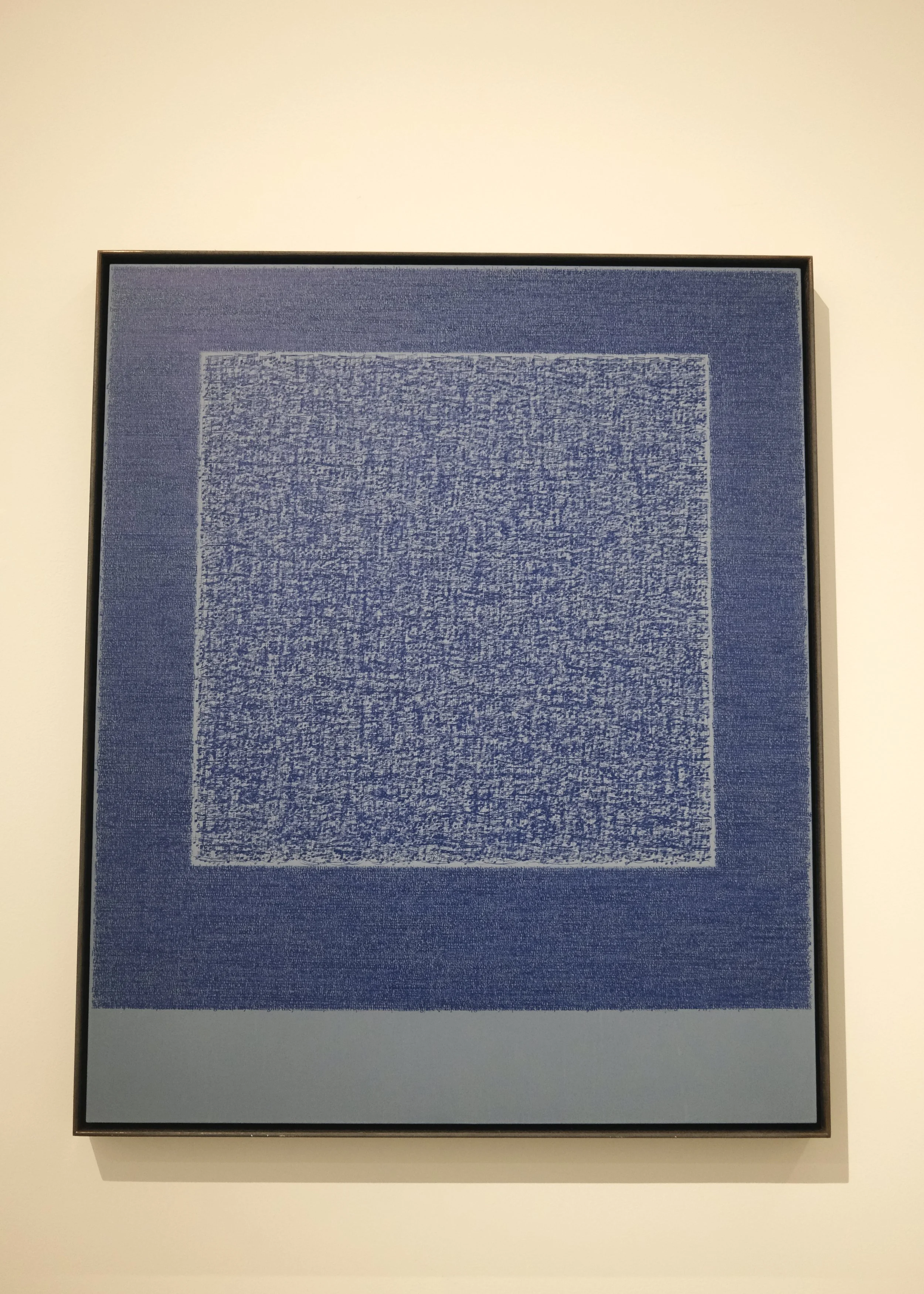

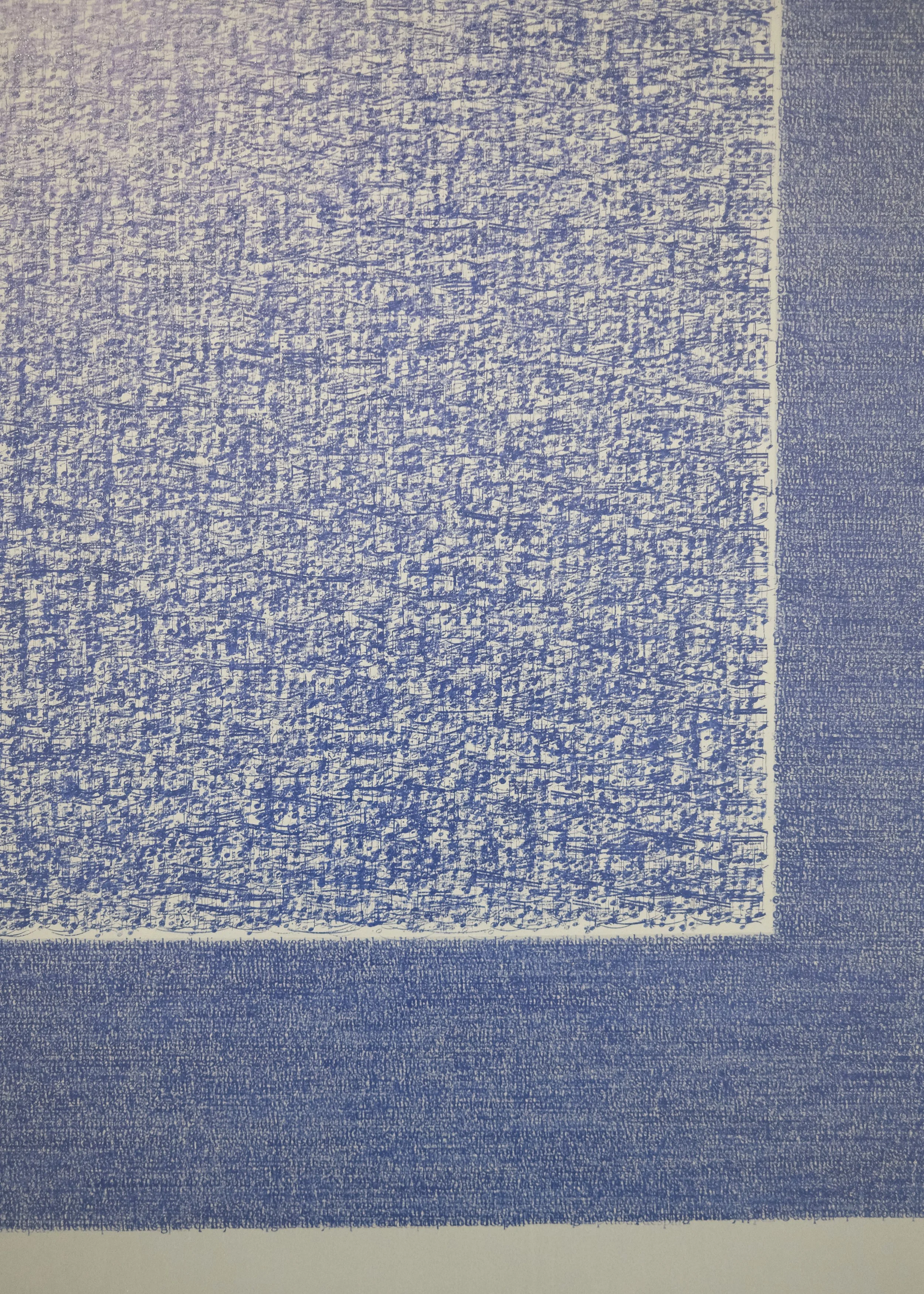

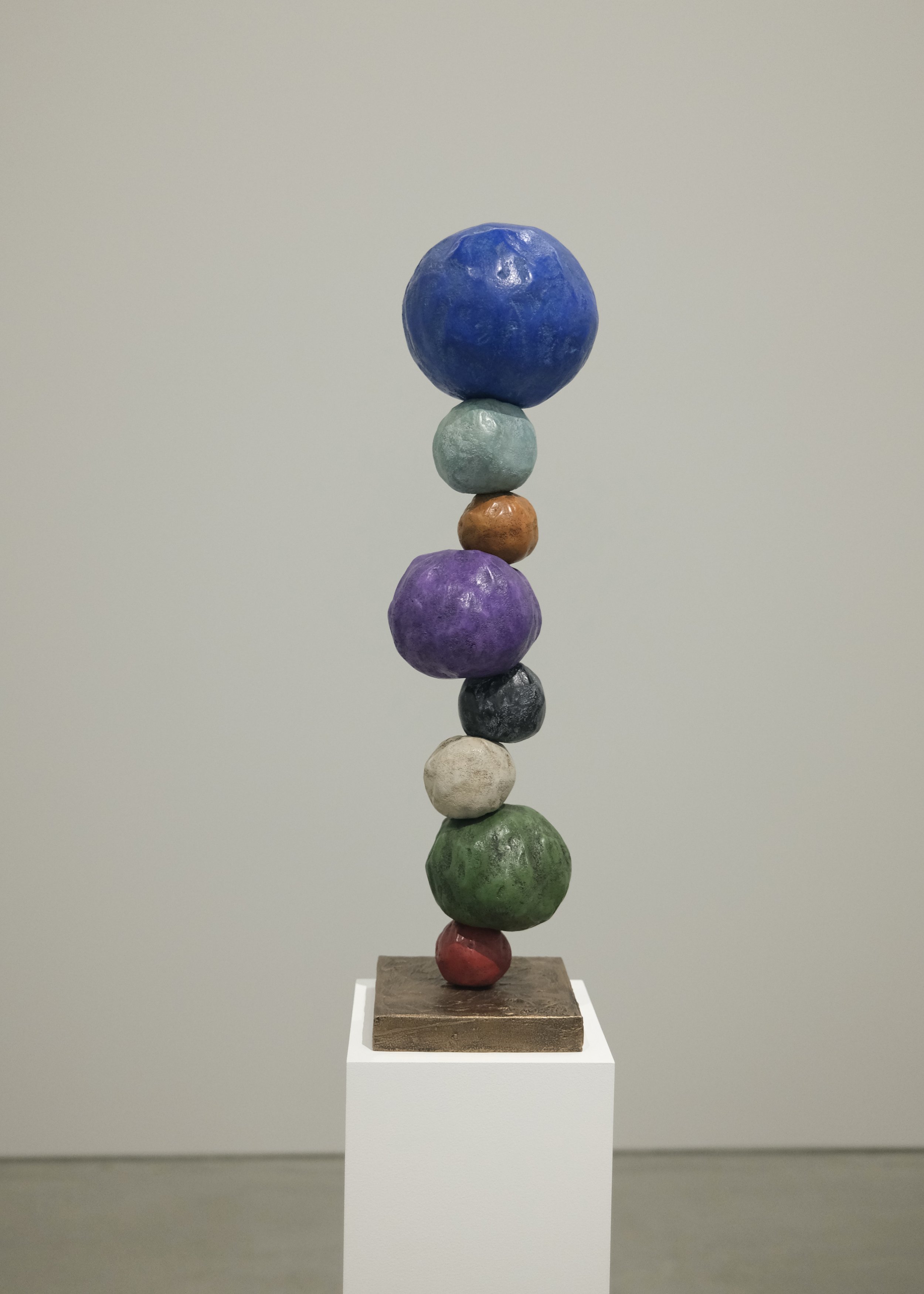

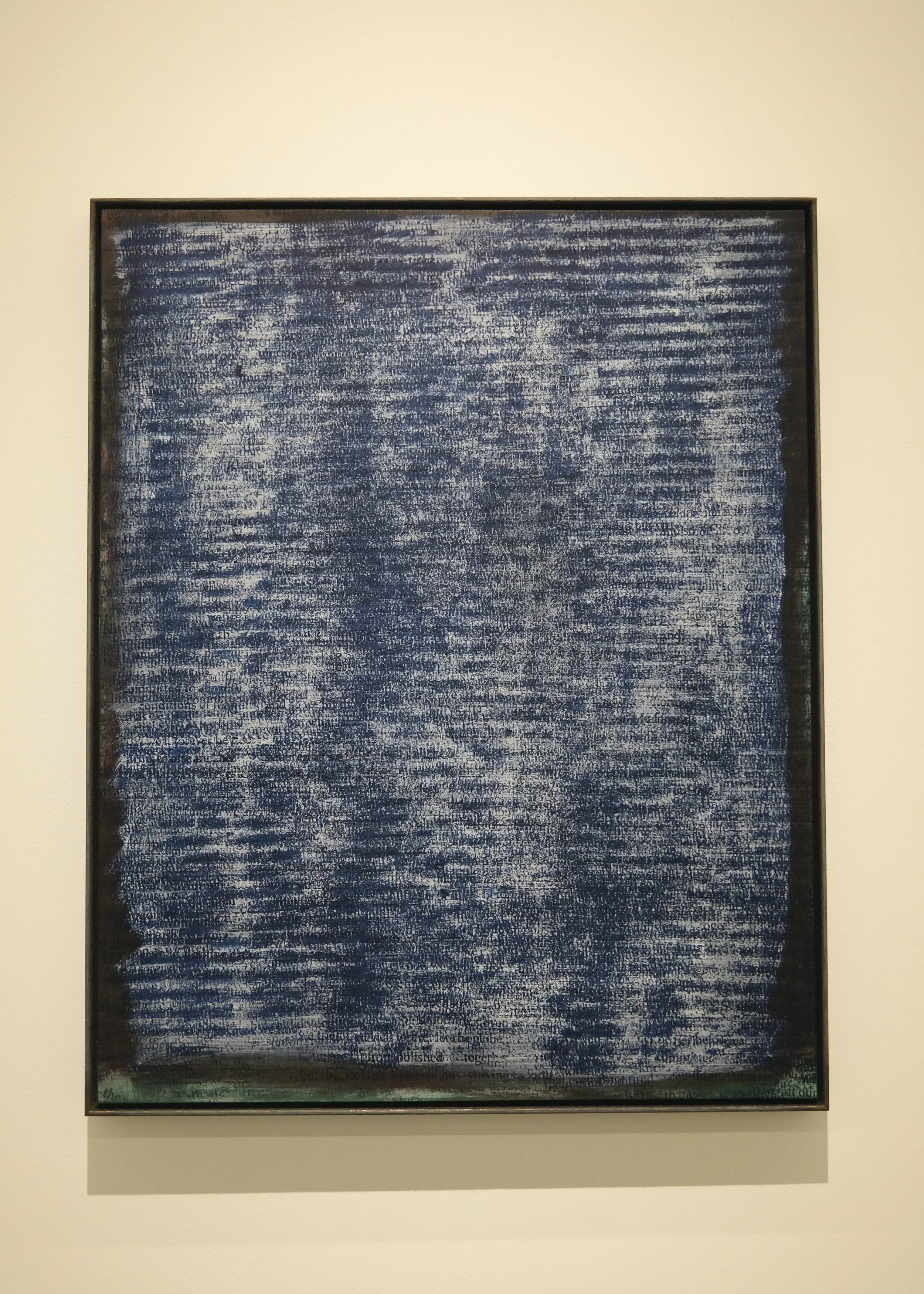

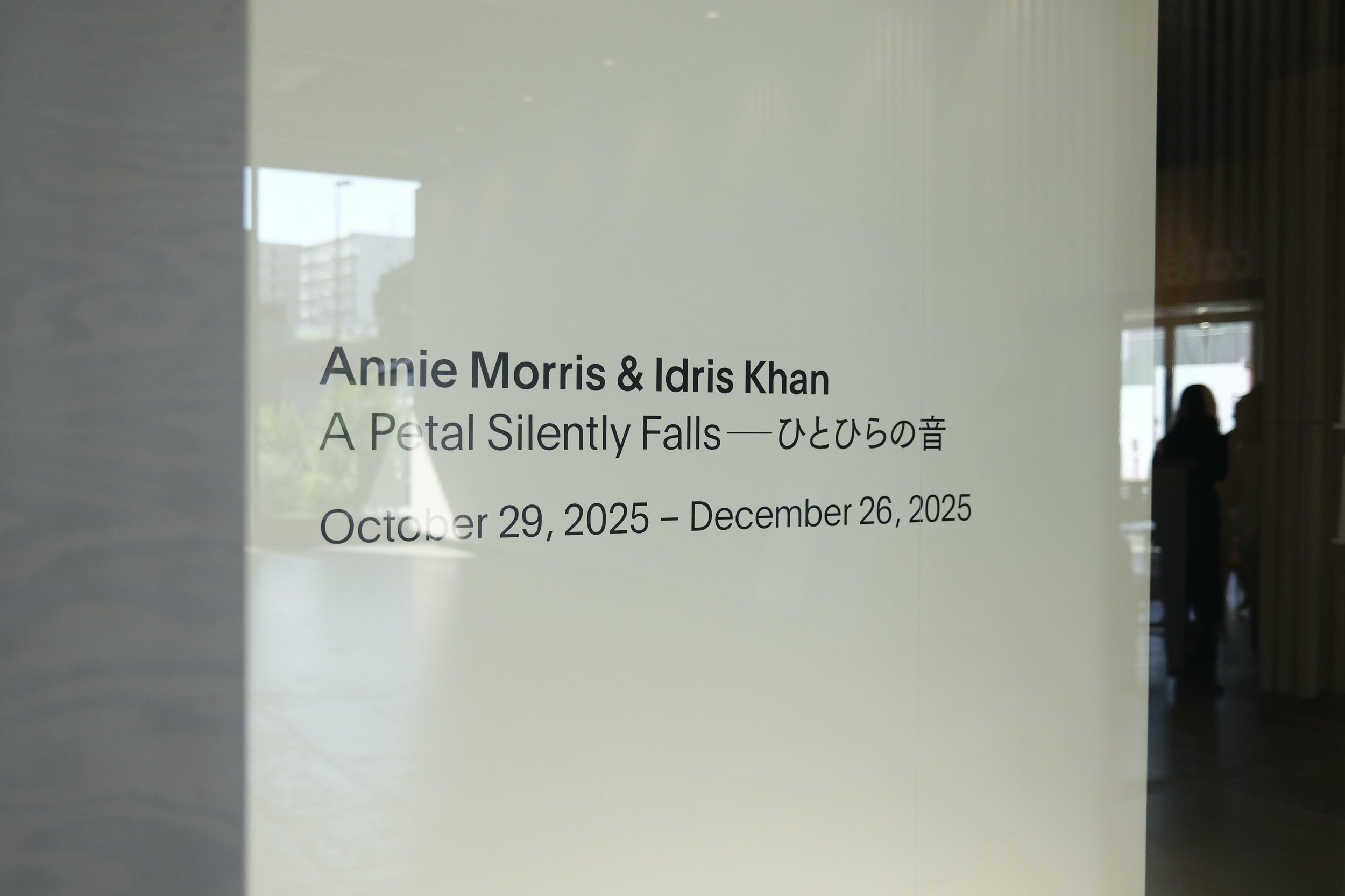

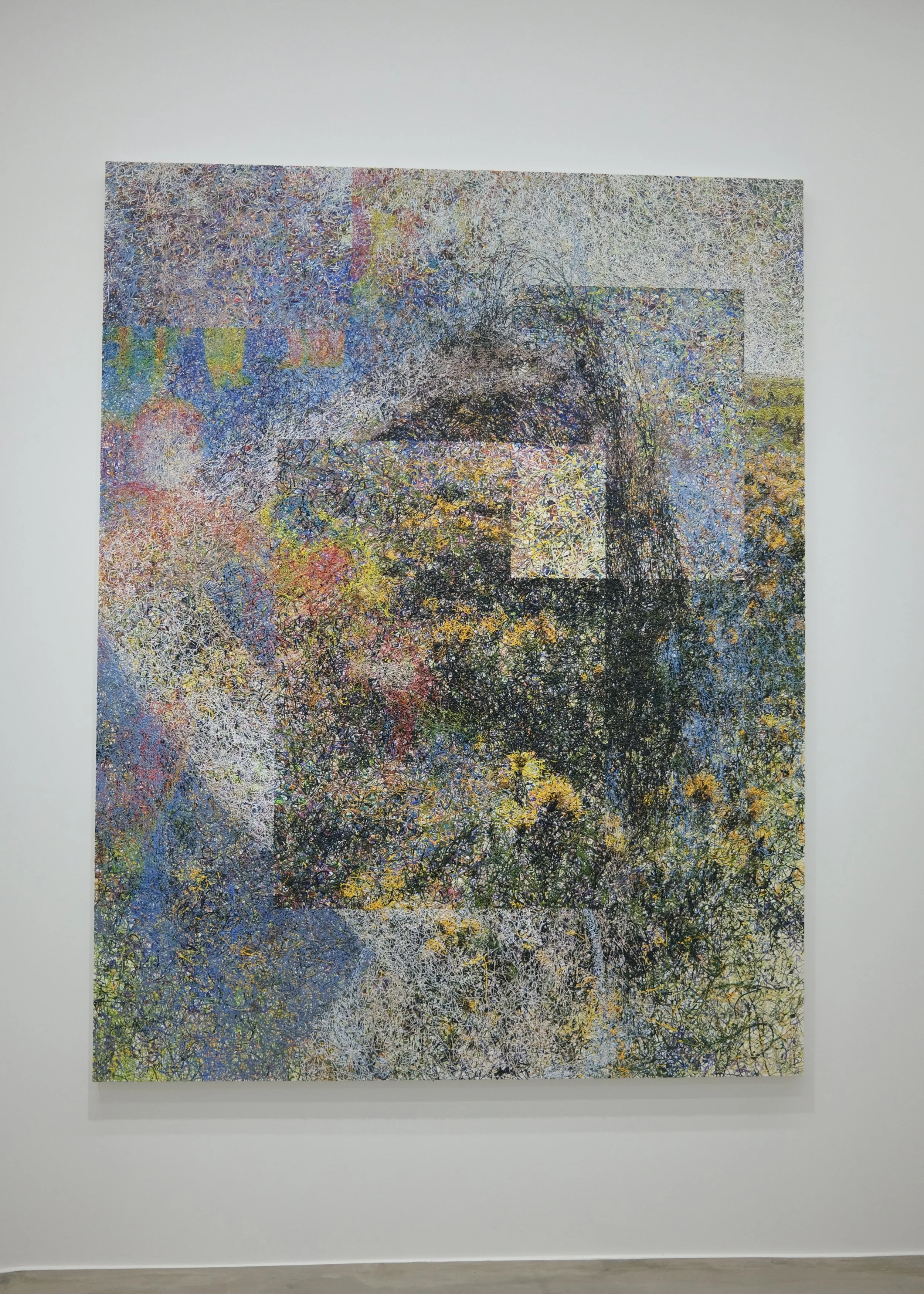

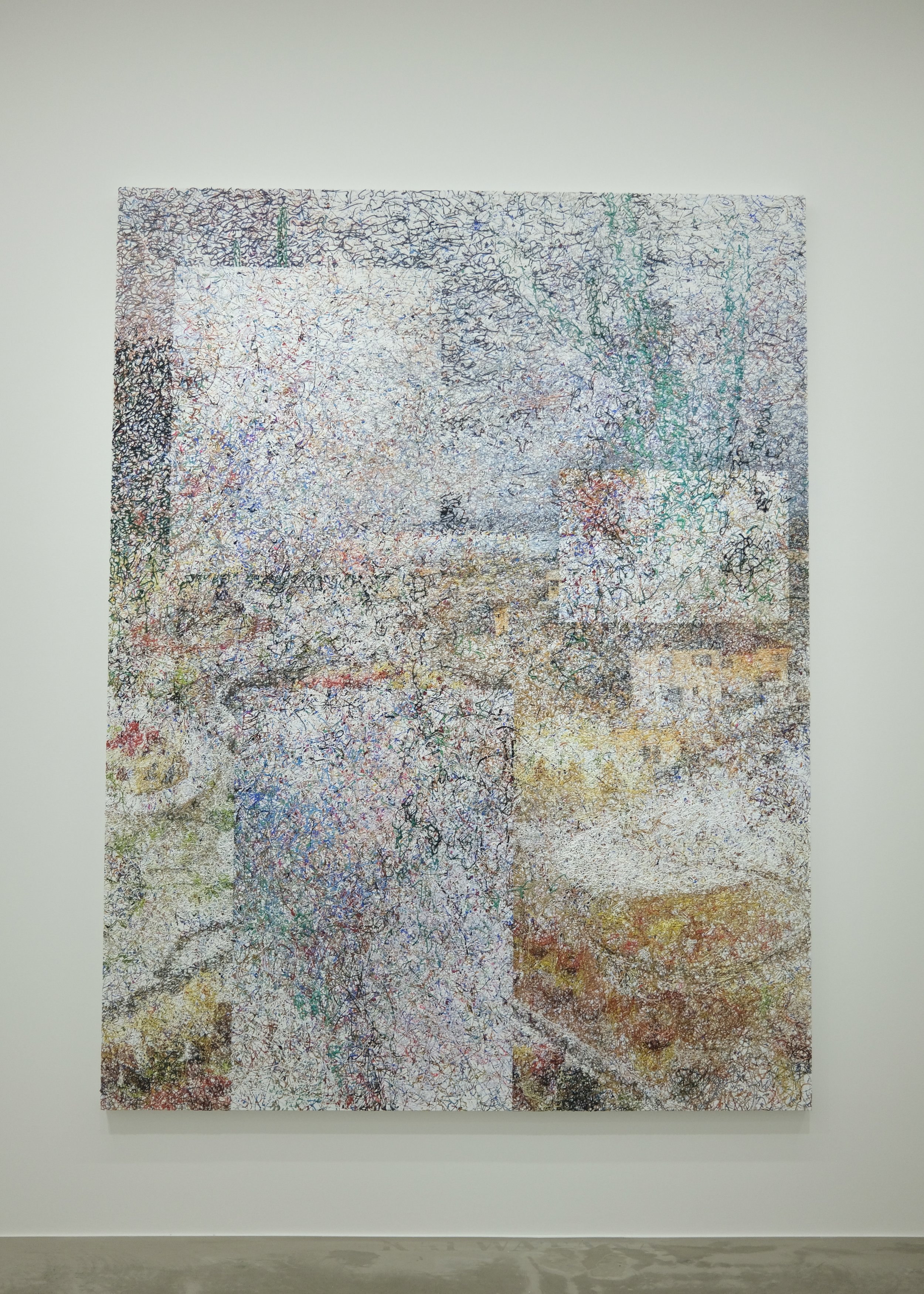

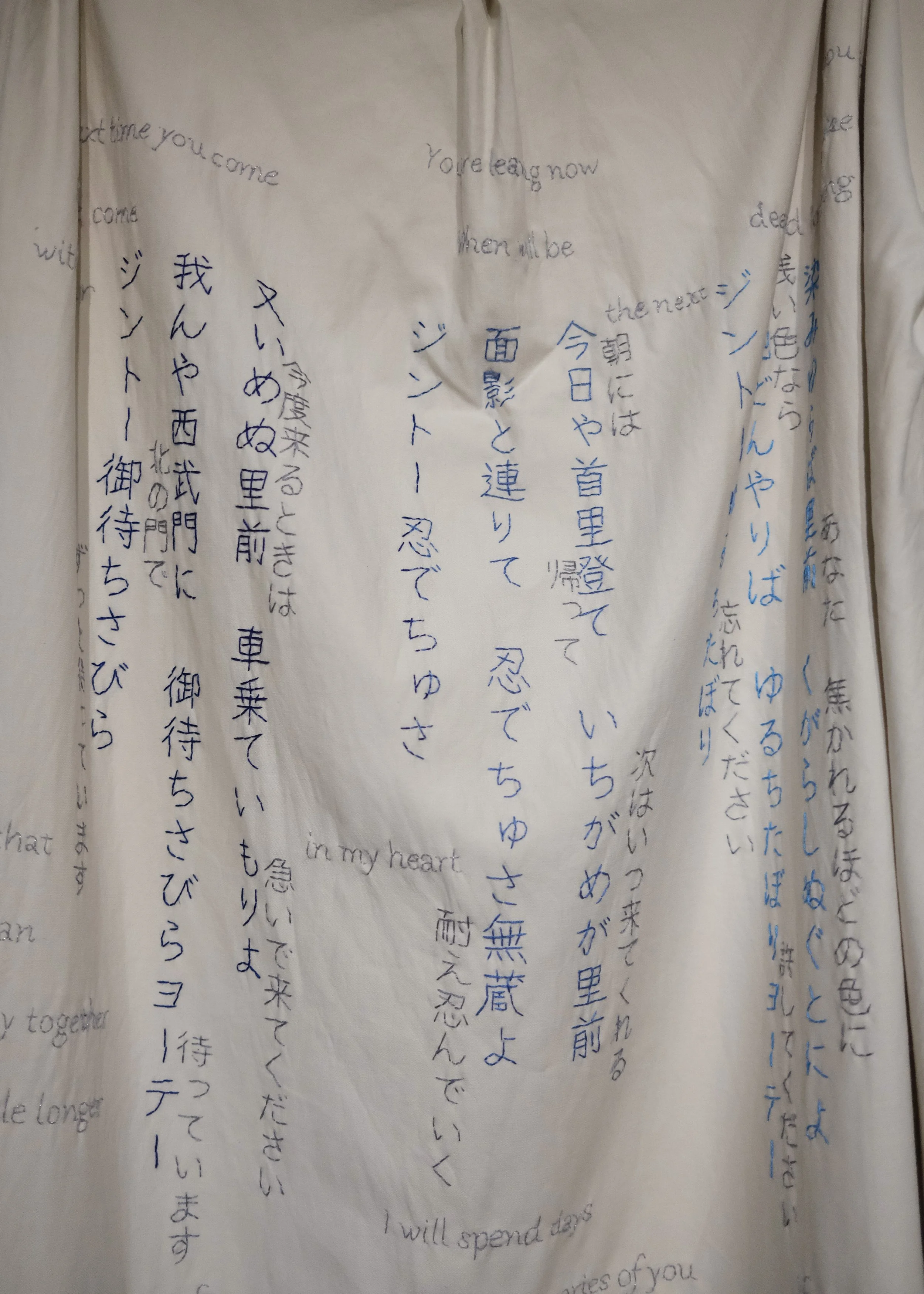

Annie Morris and Idris Khan A Petal Silently Falls

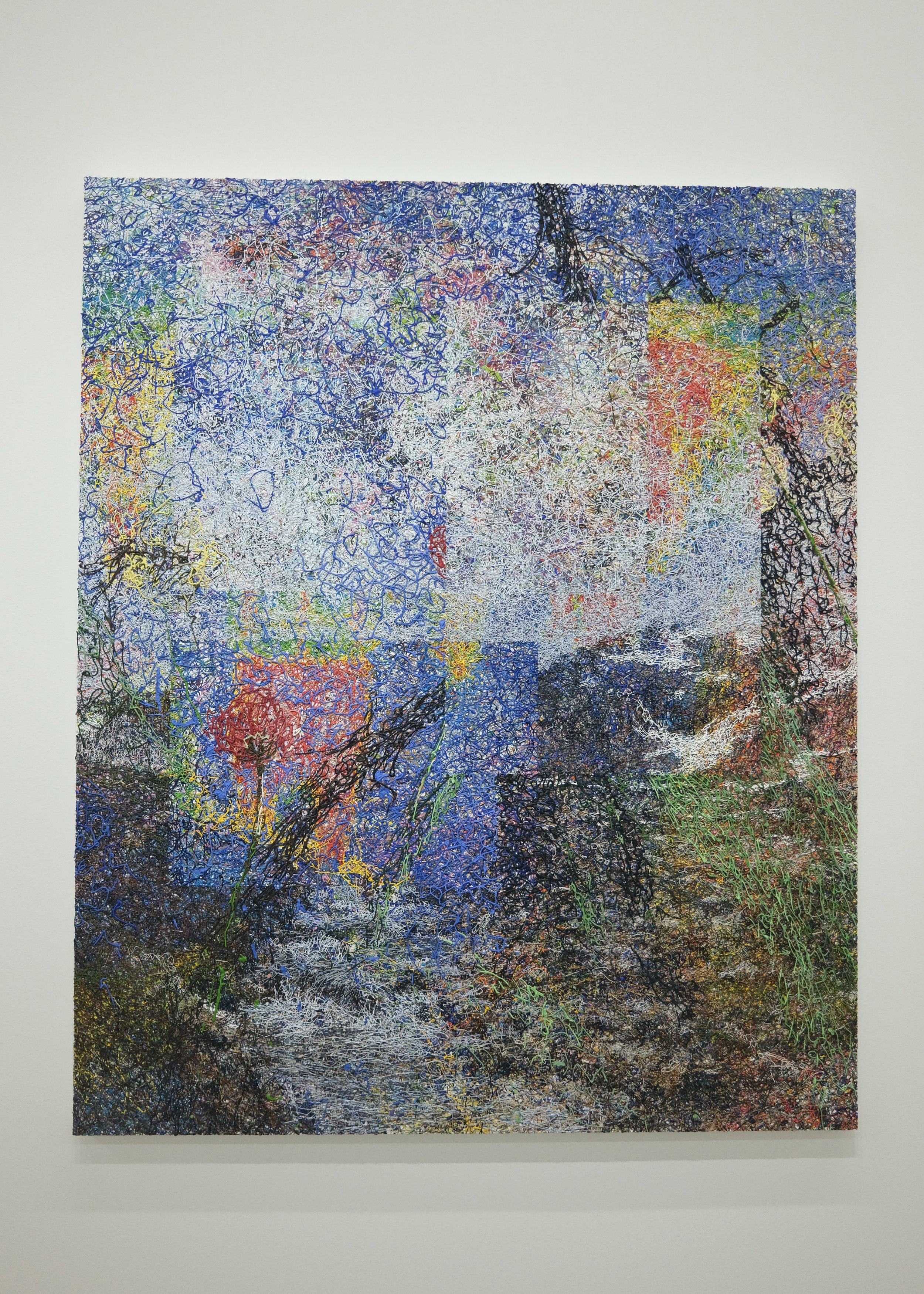

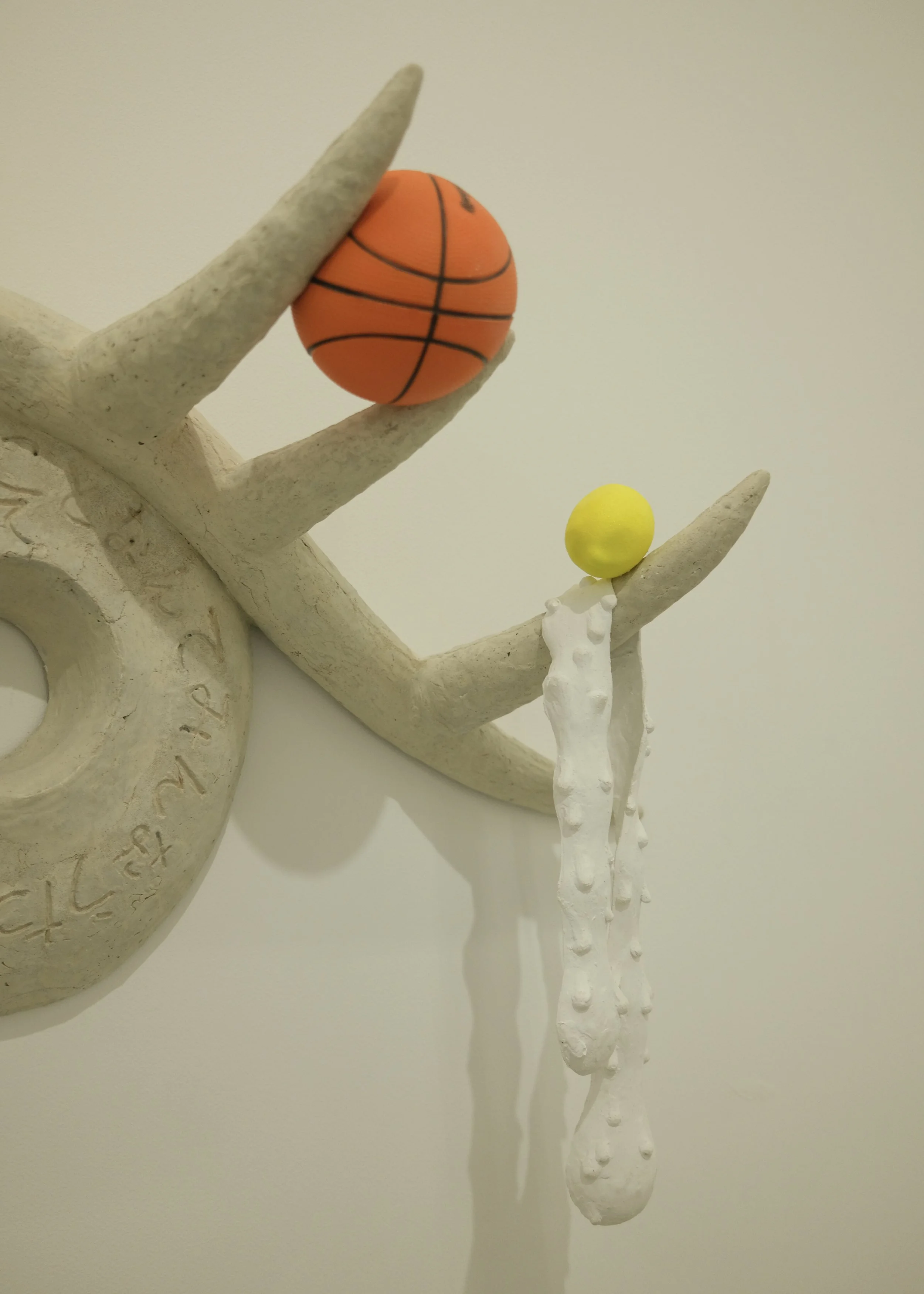

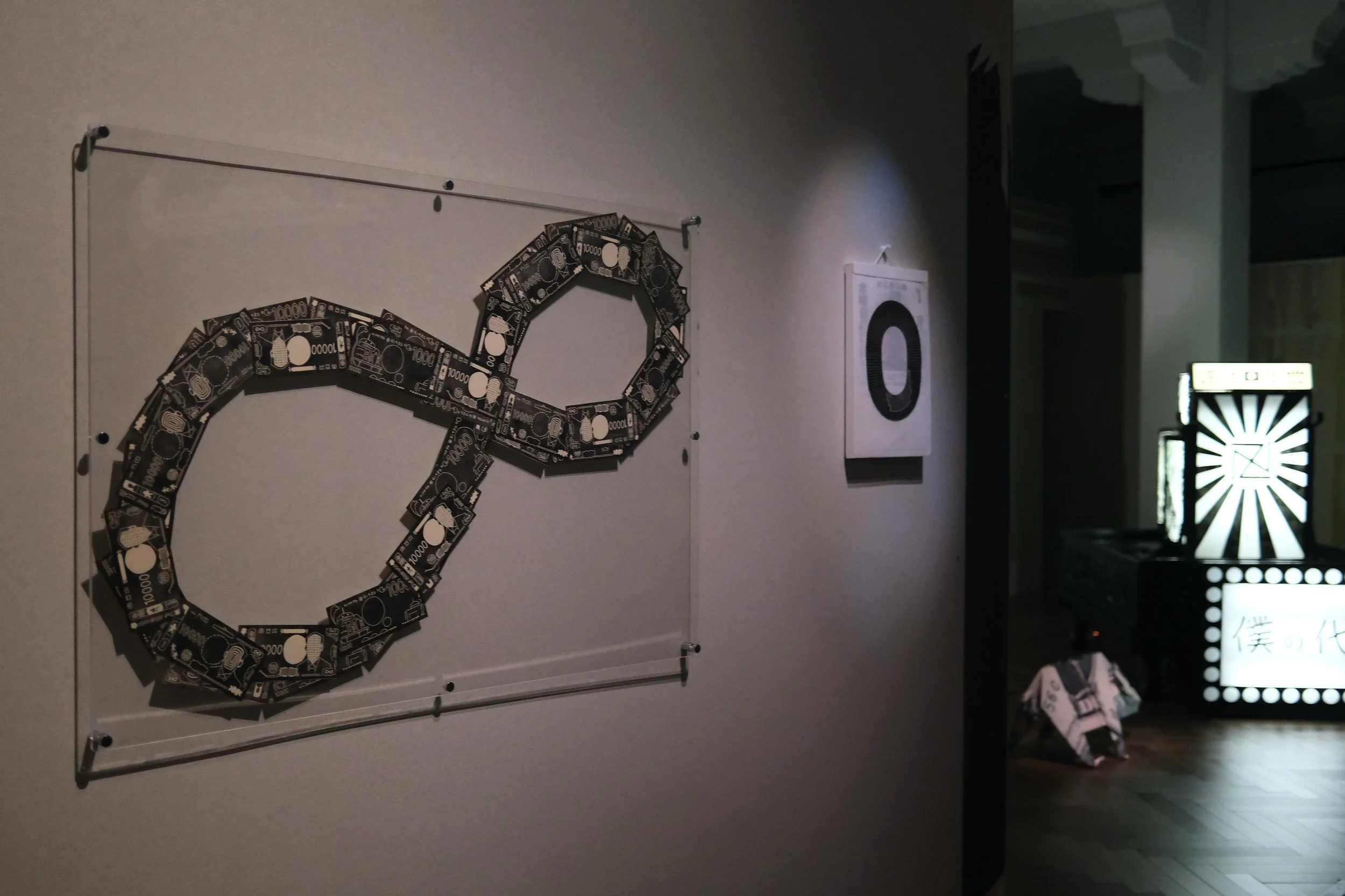

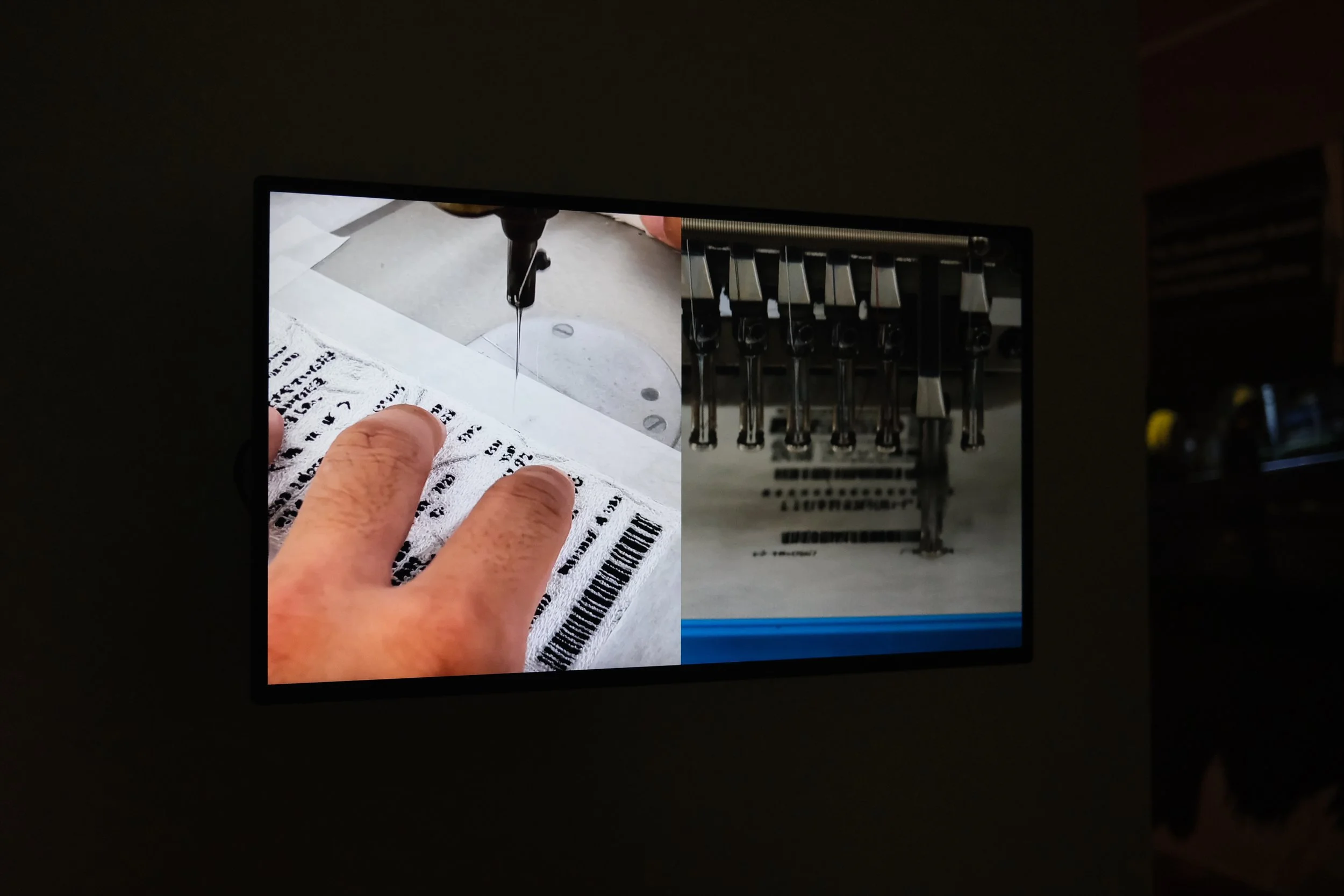

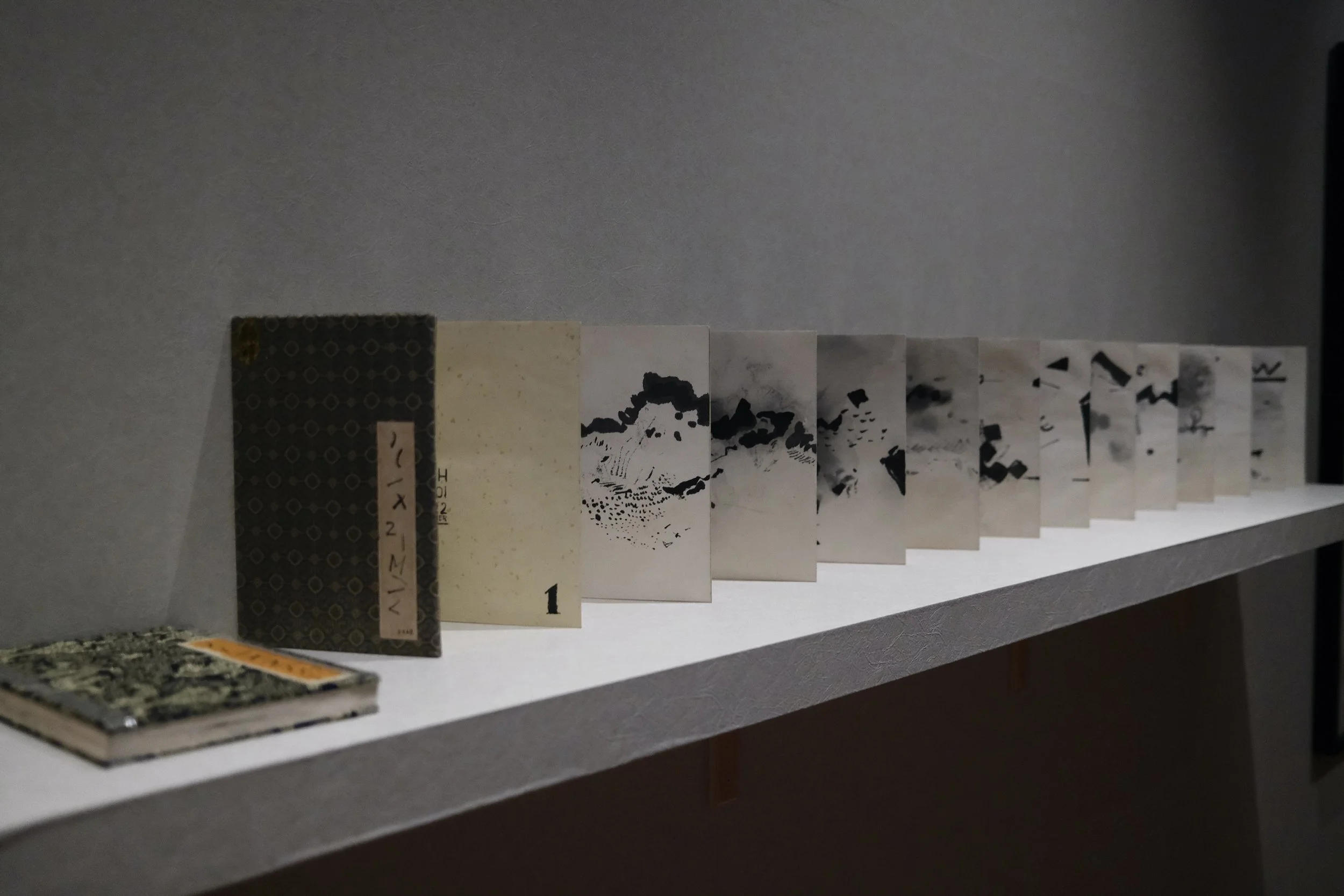

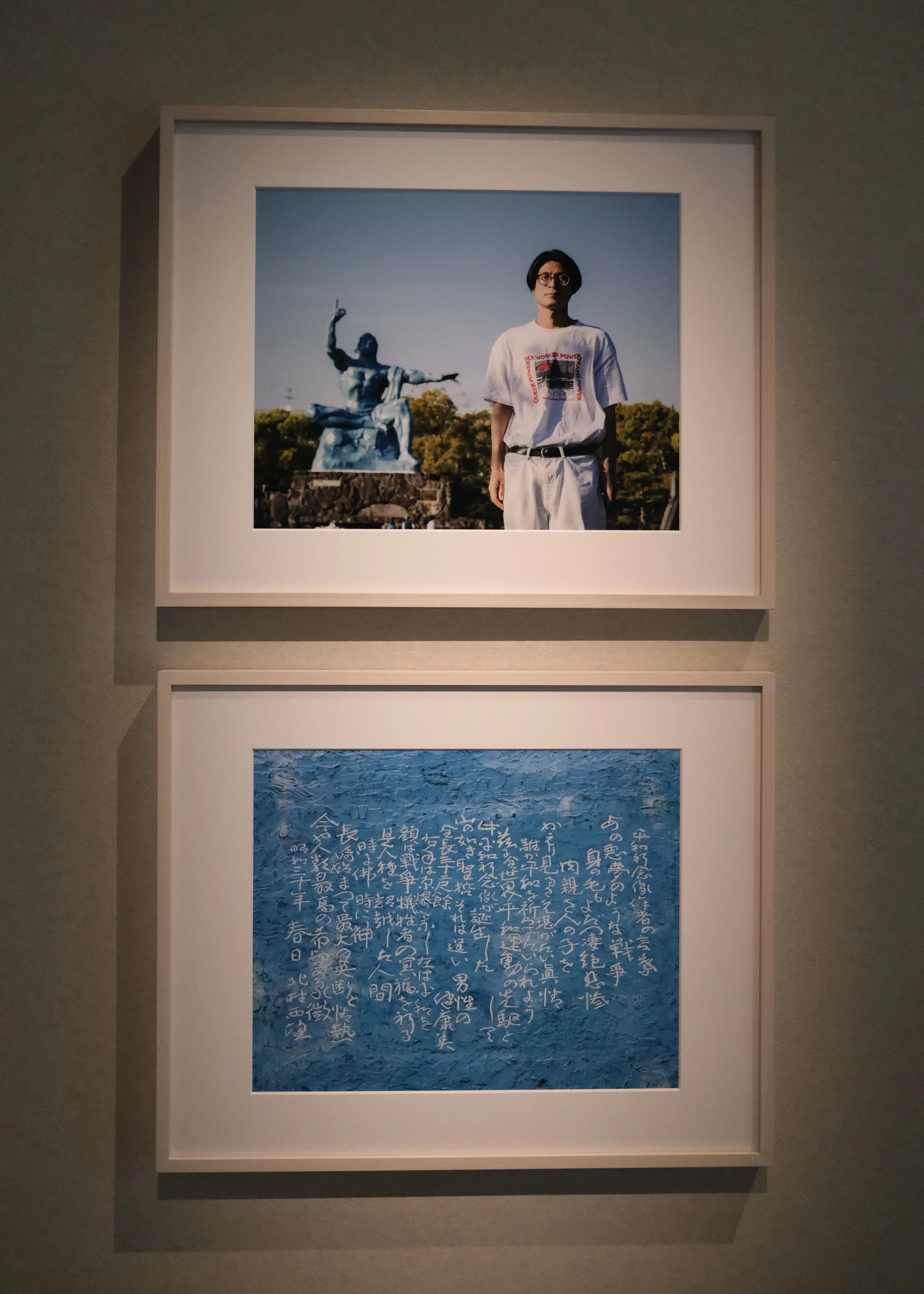

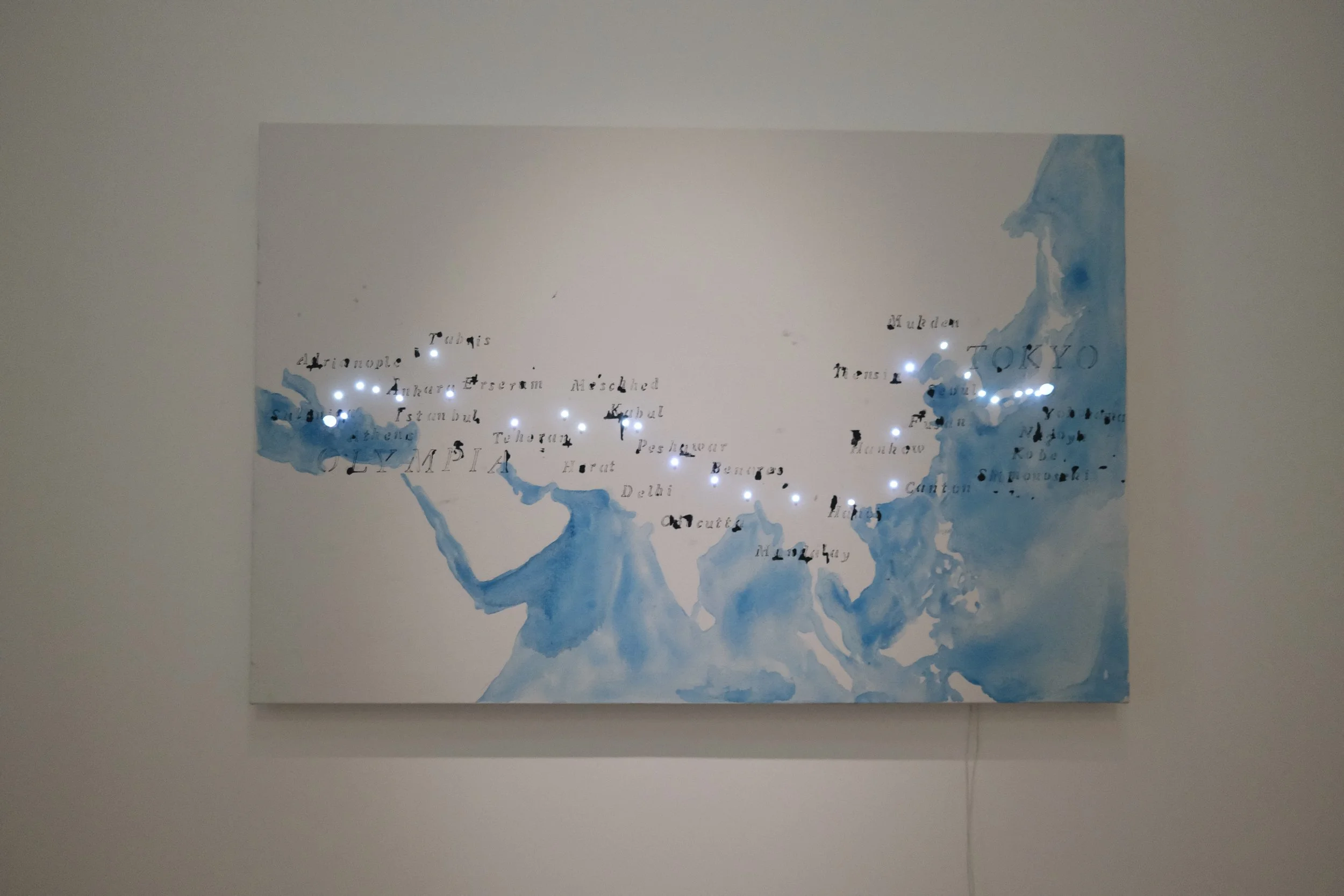

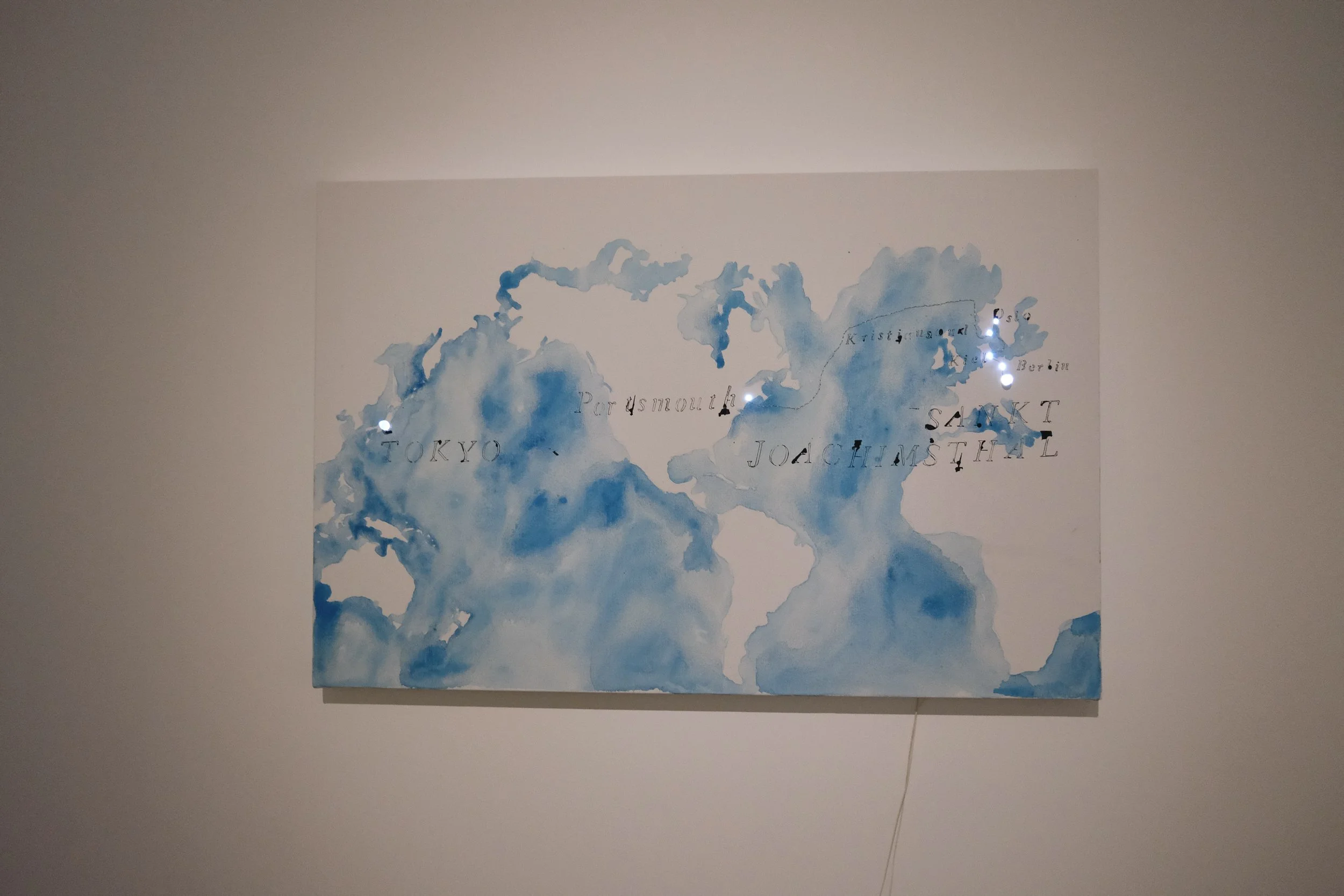

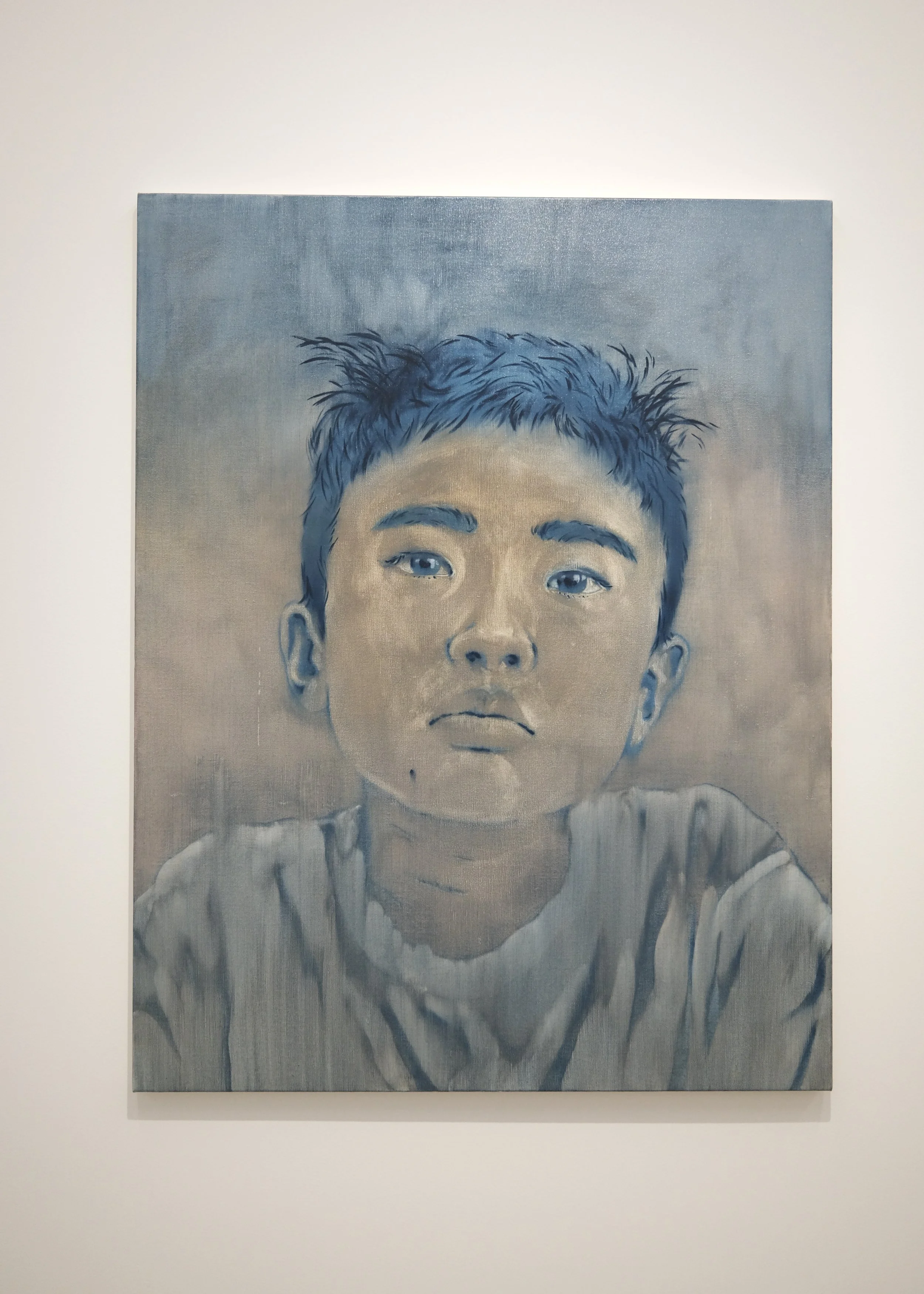

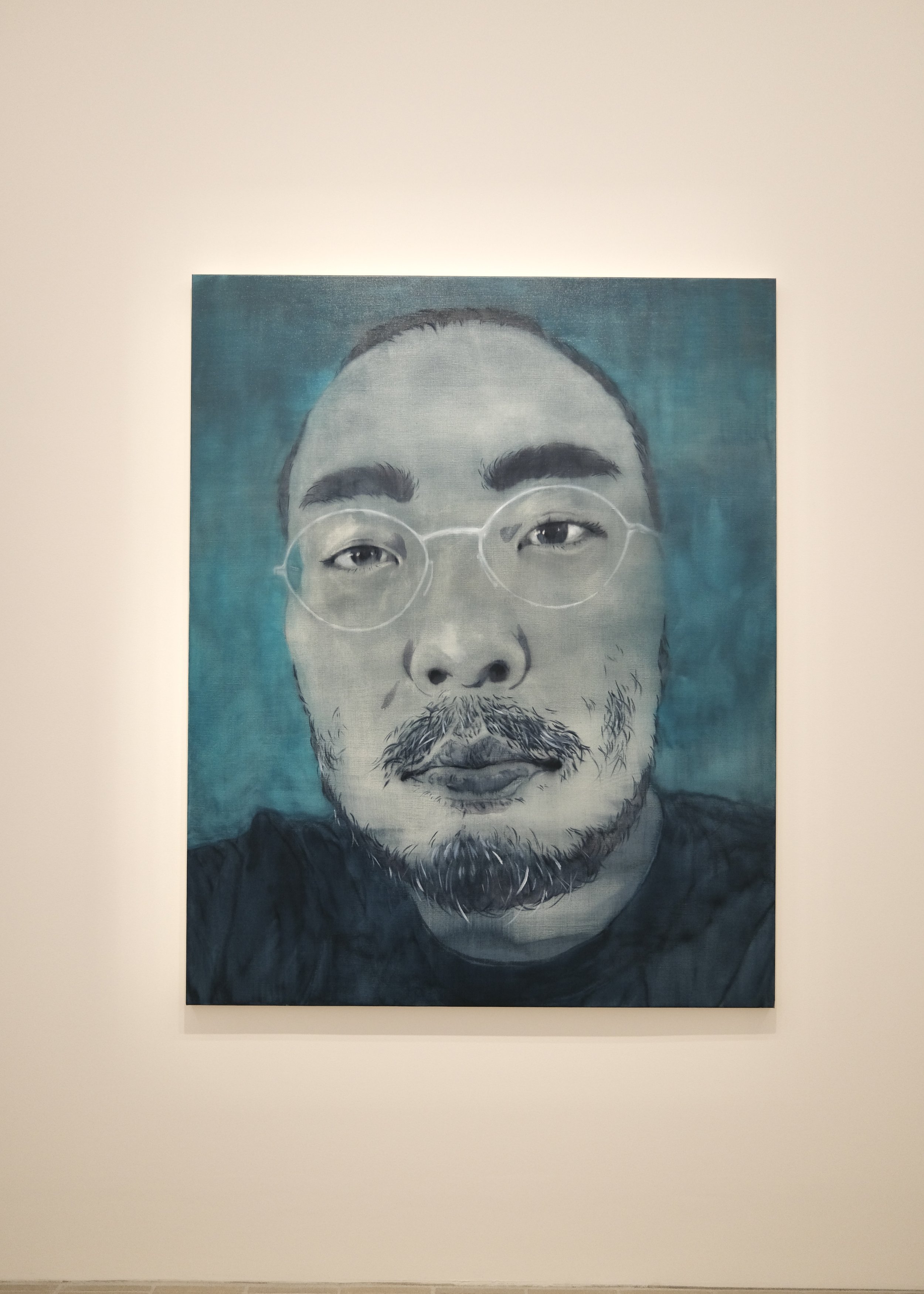

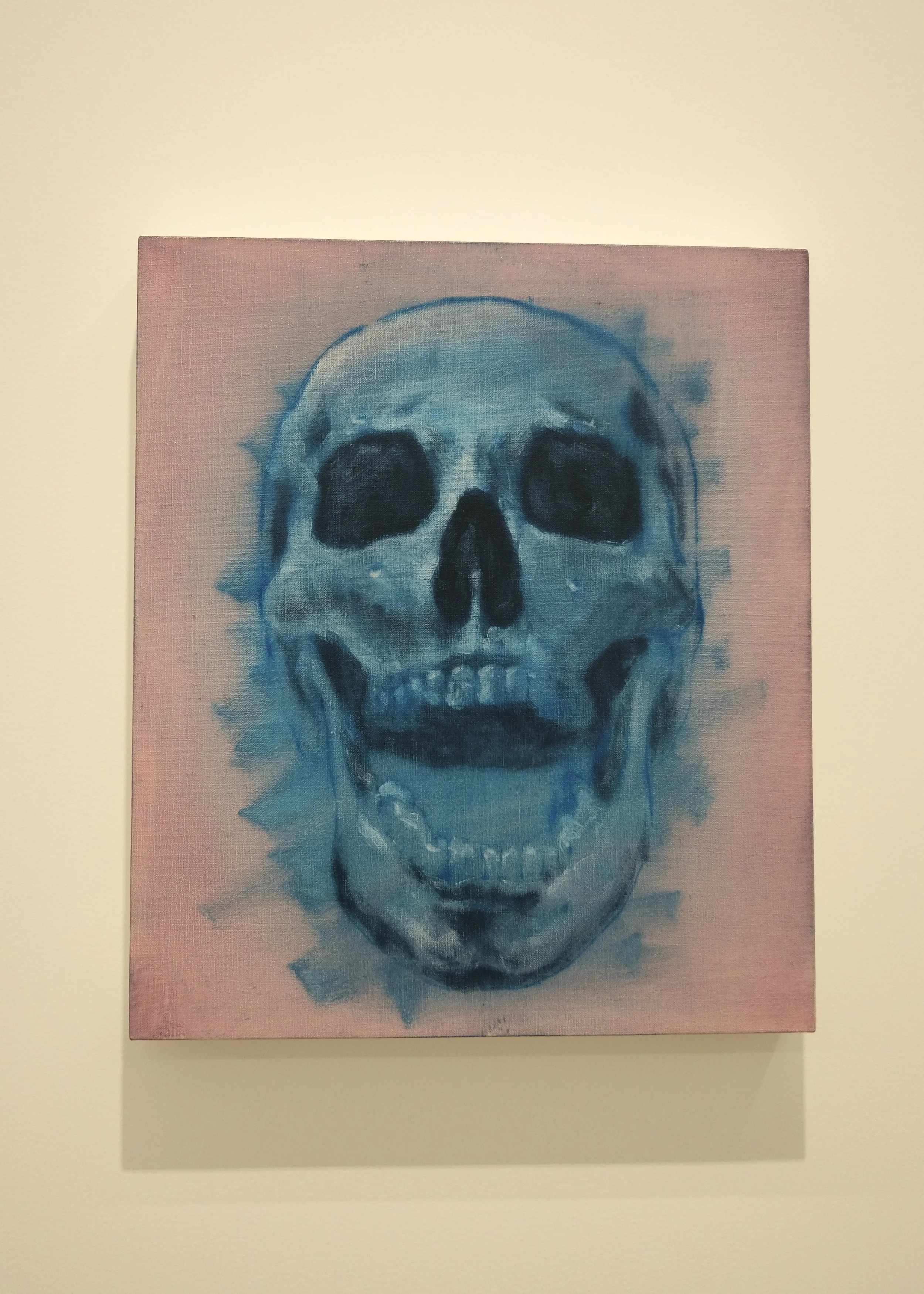

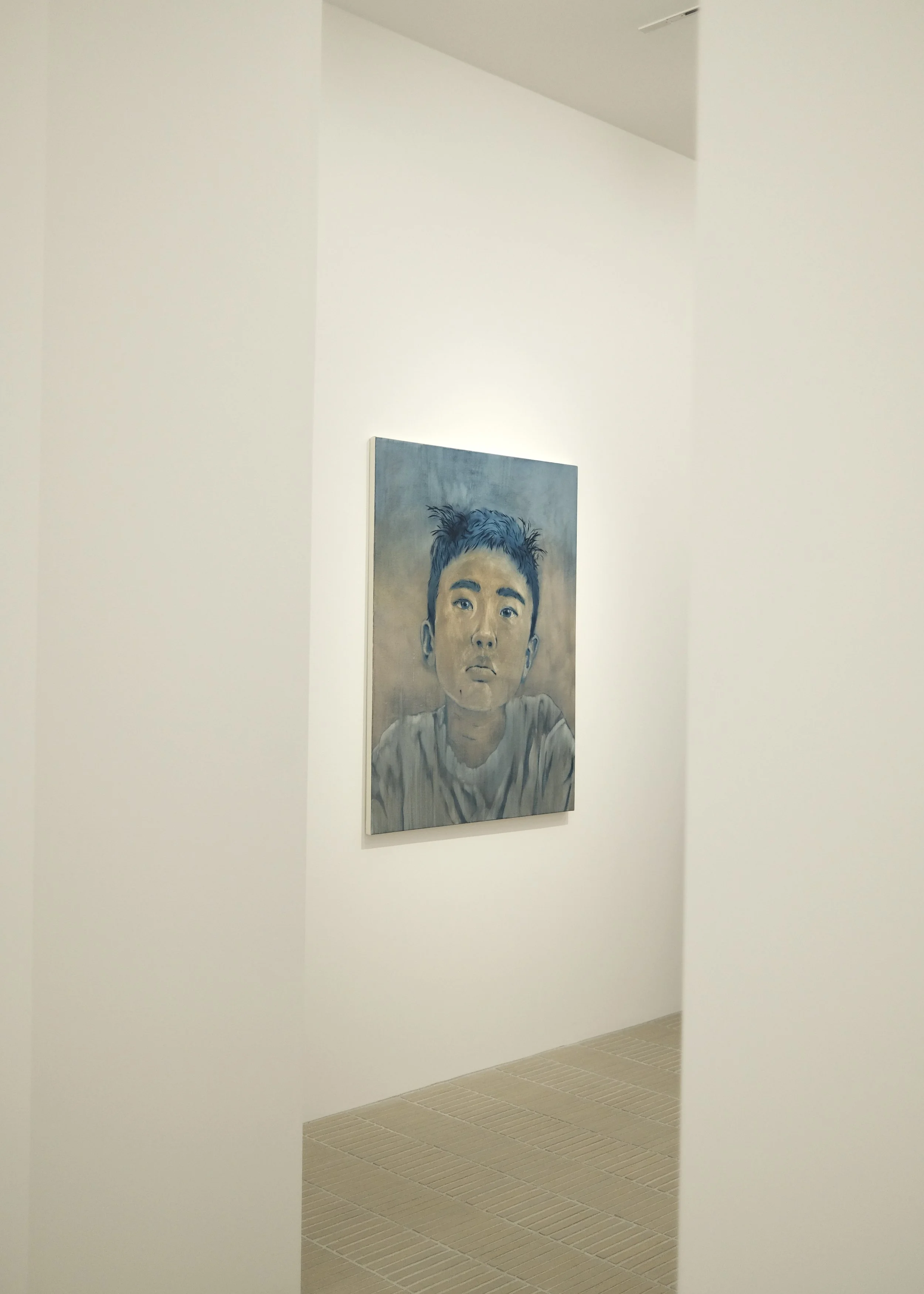

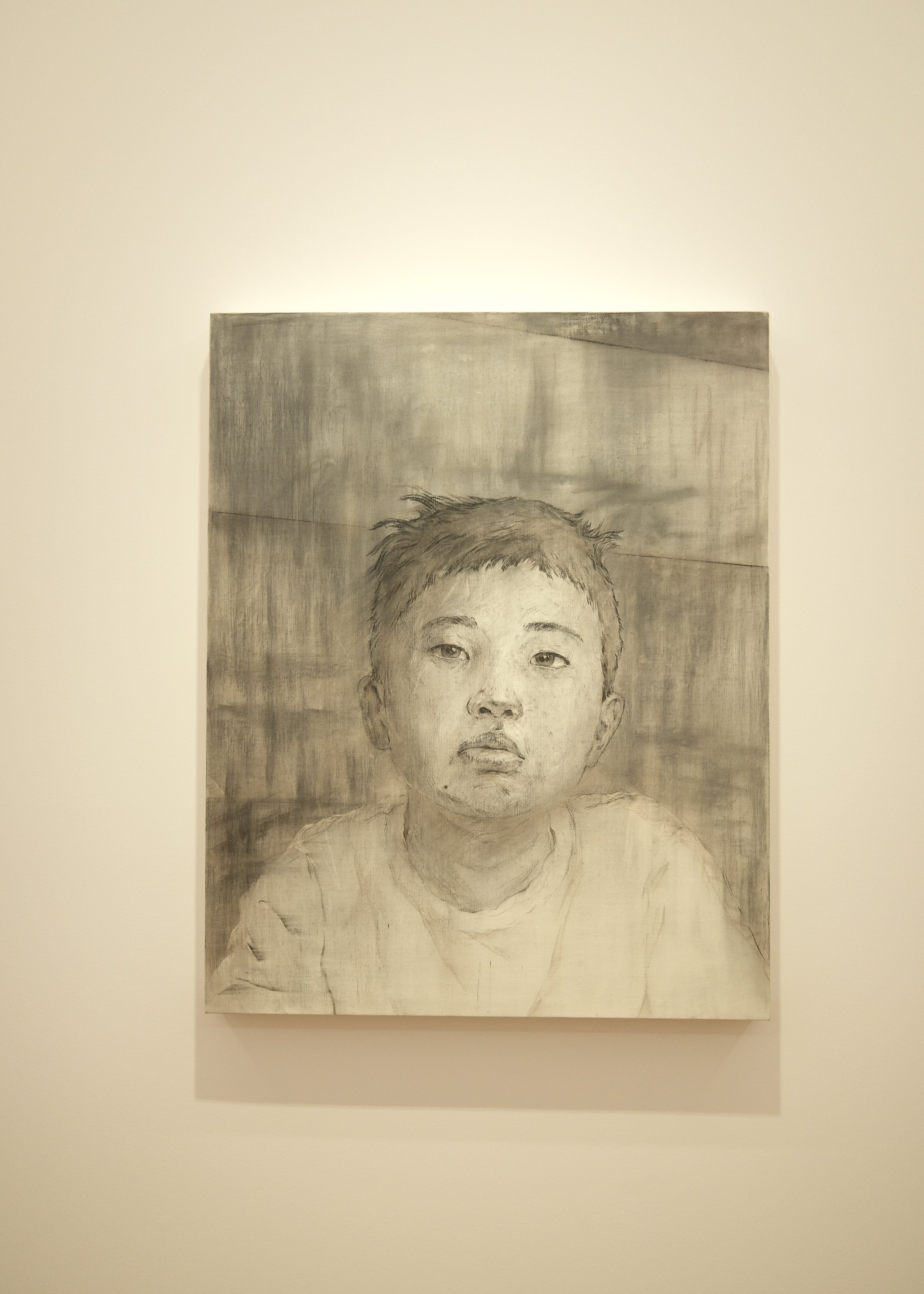

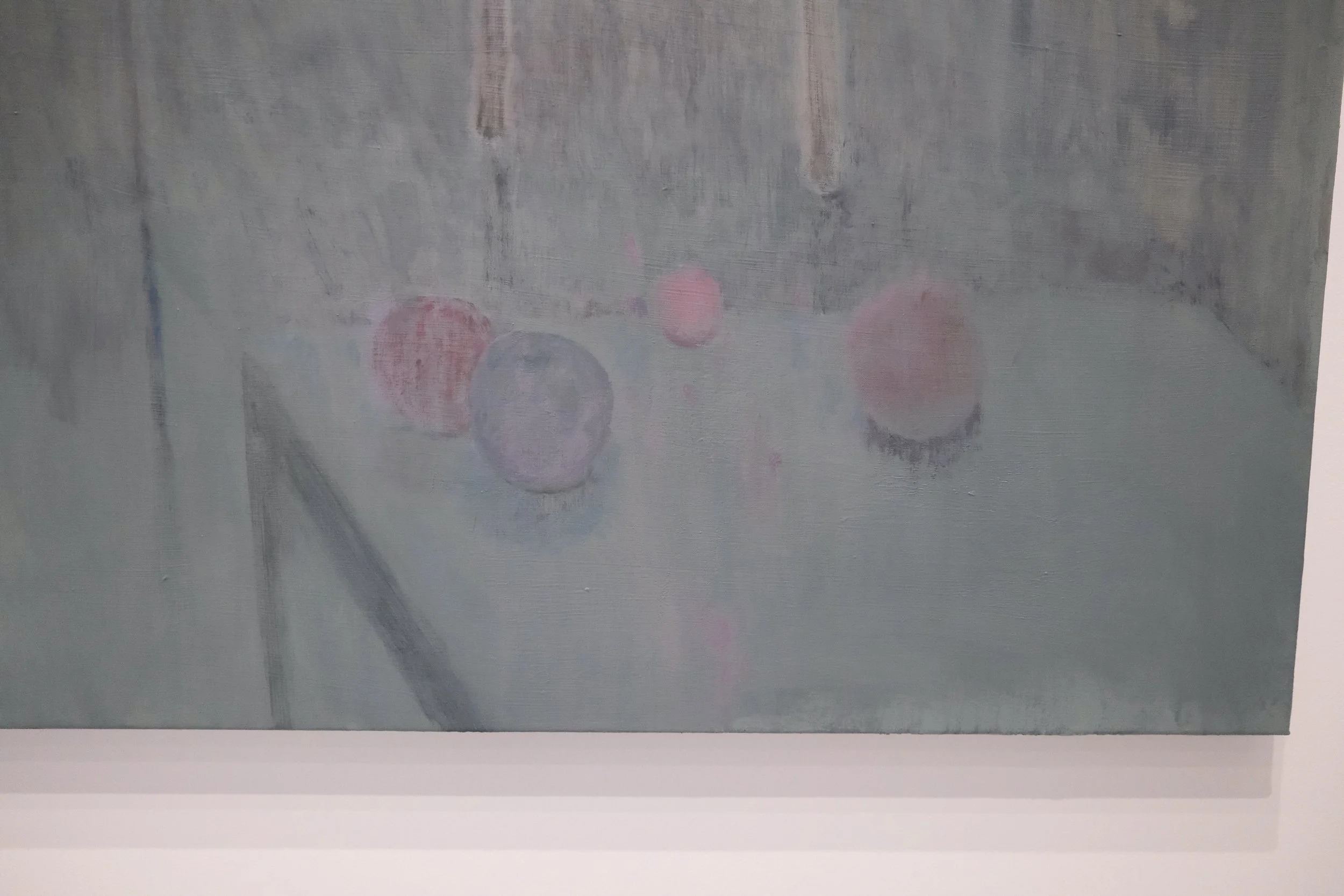

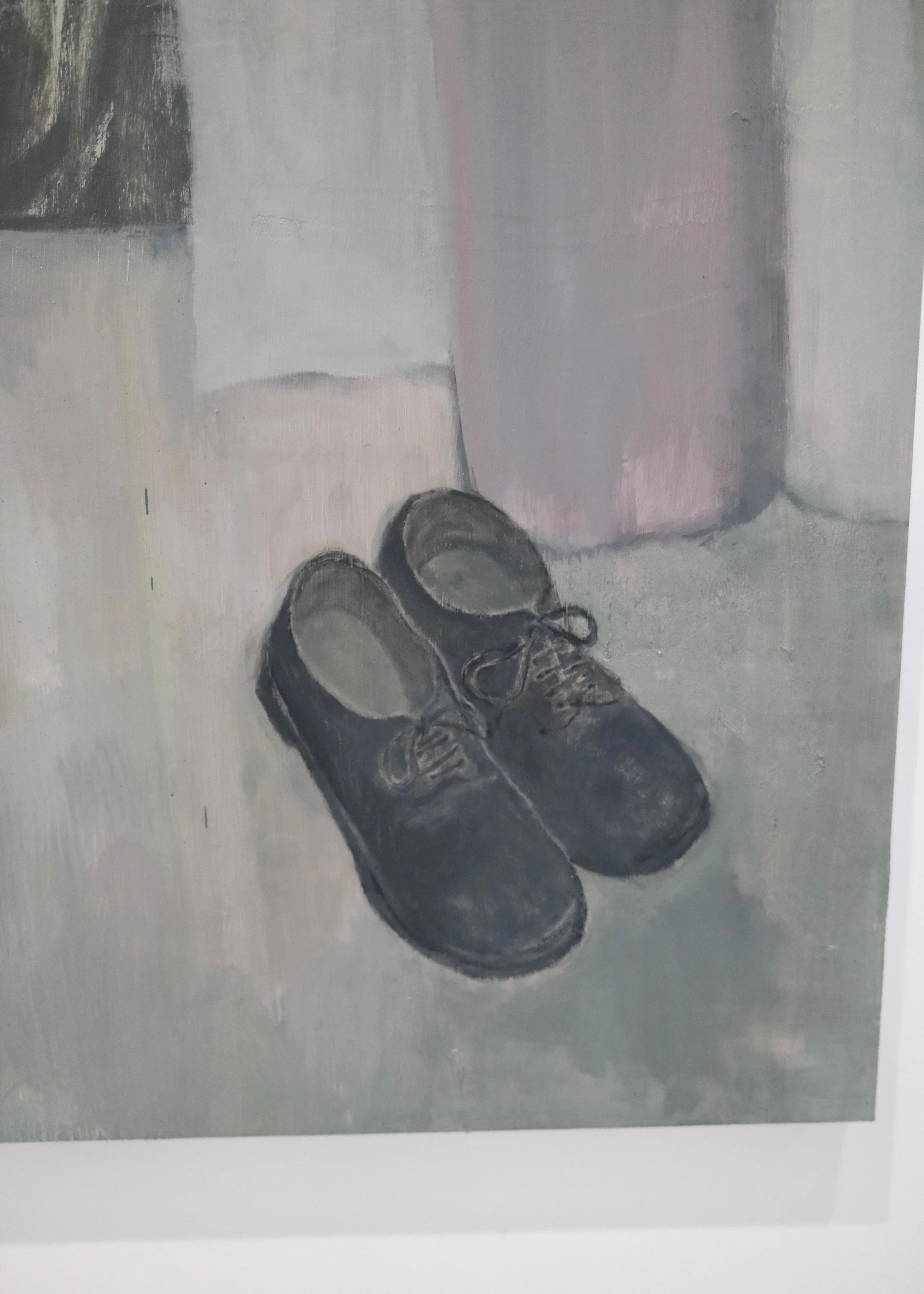

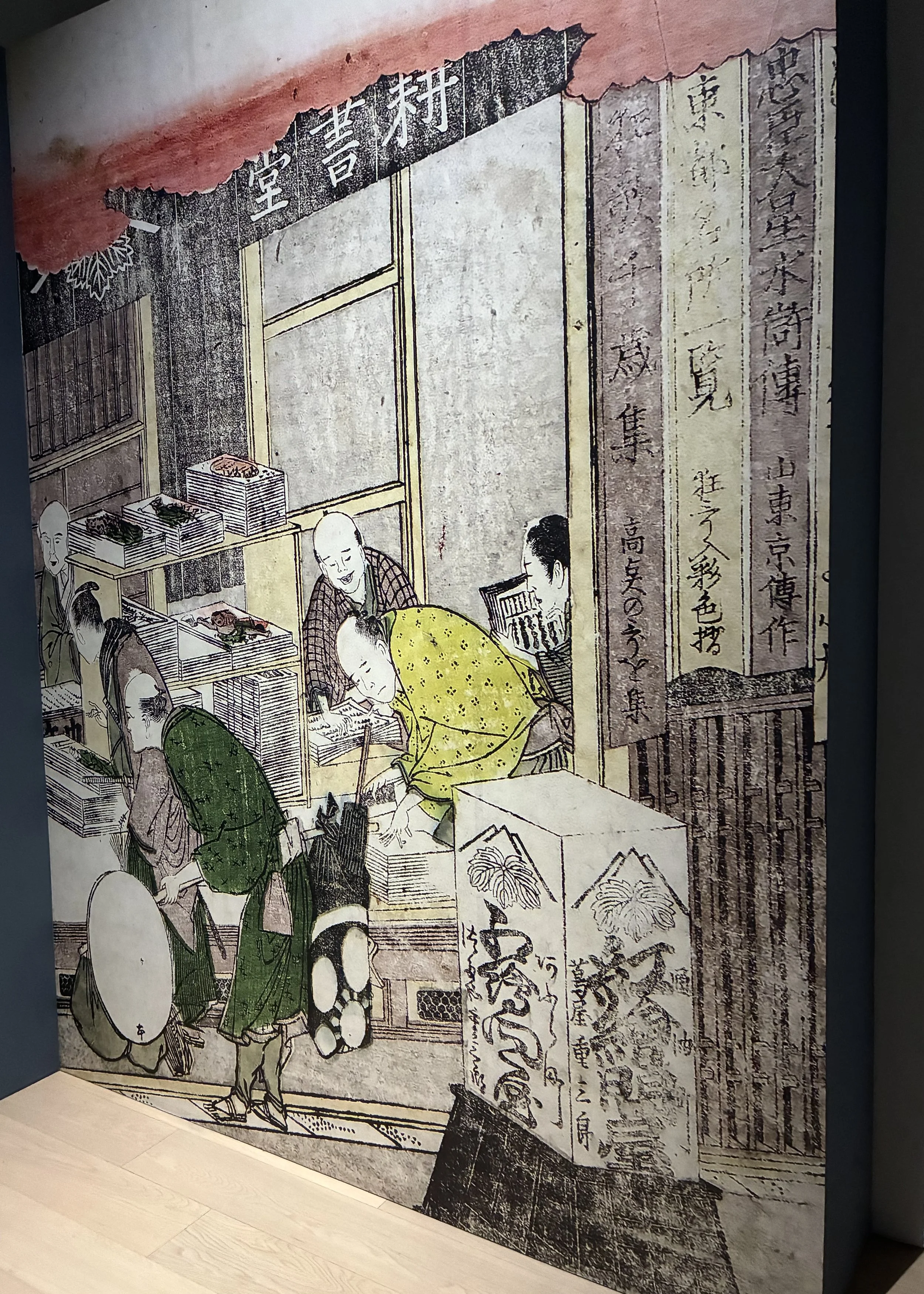

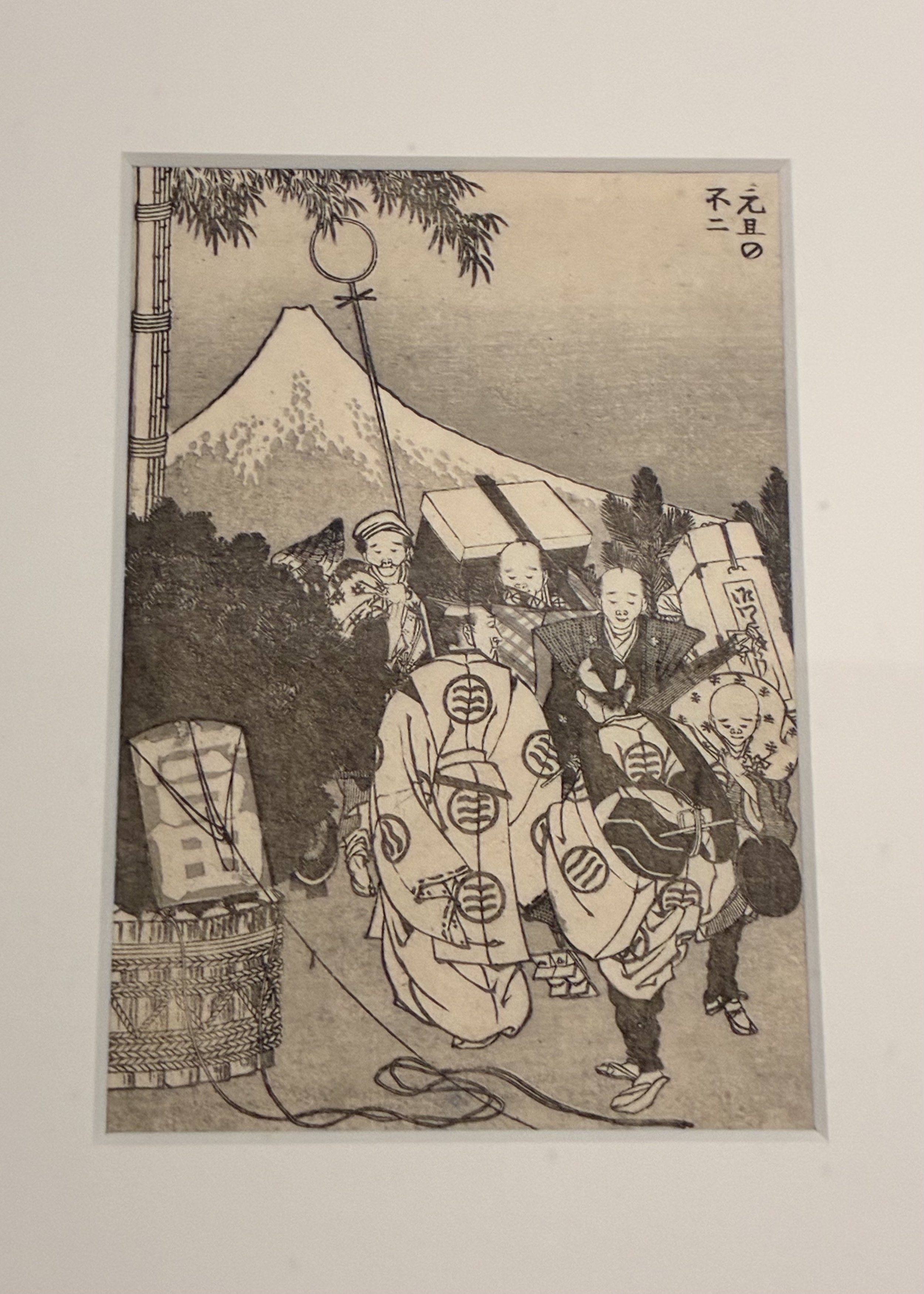

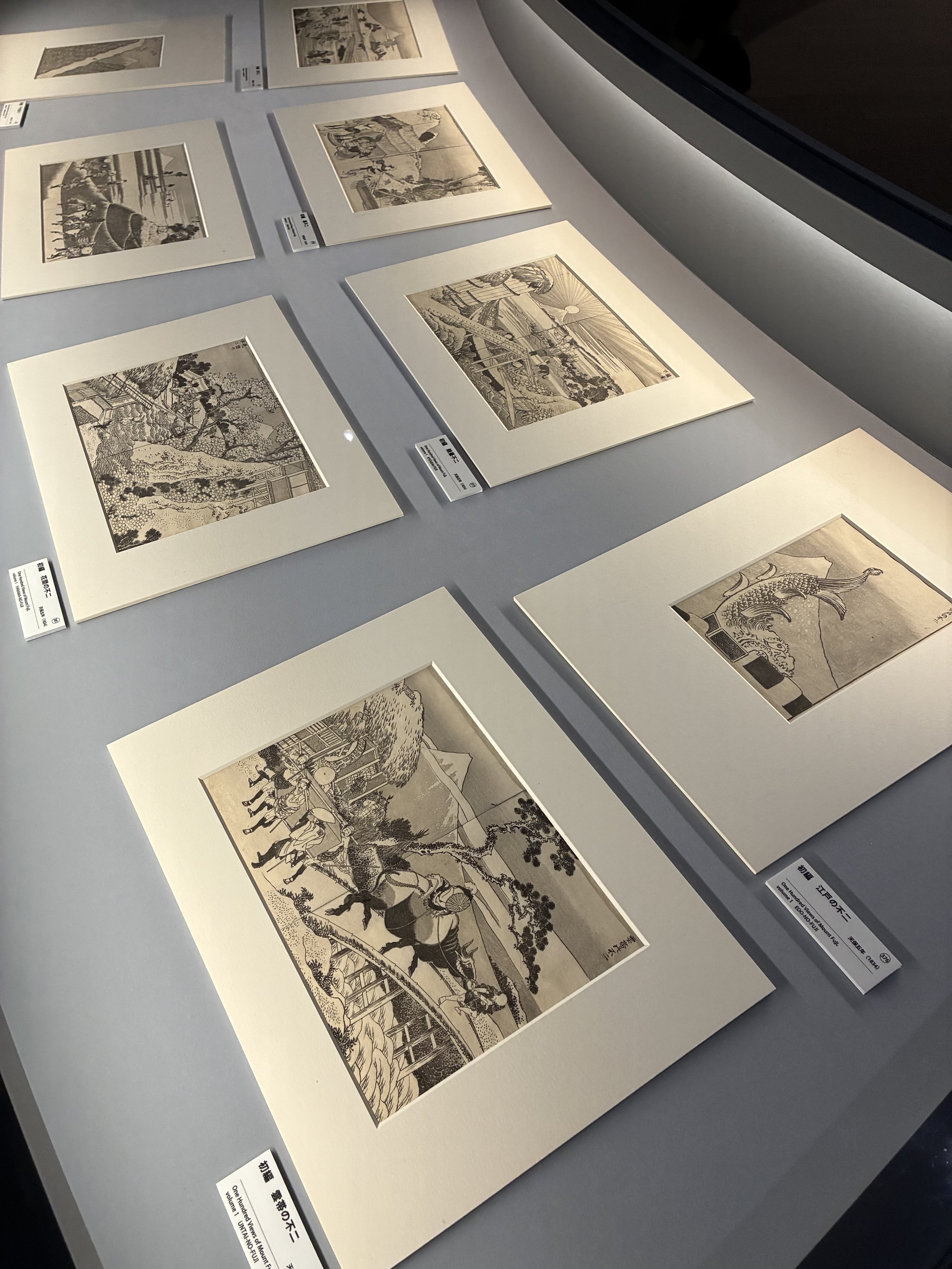

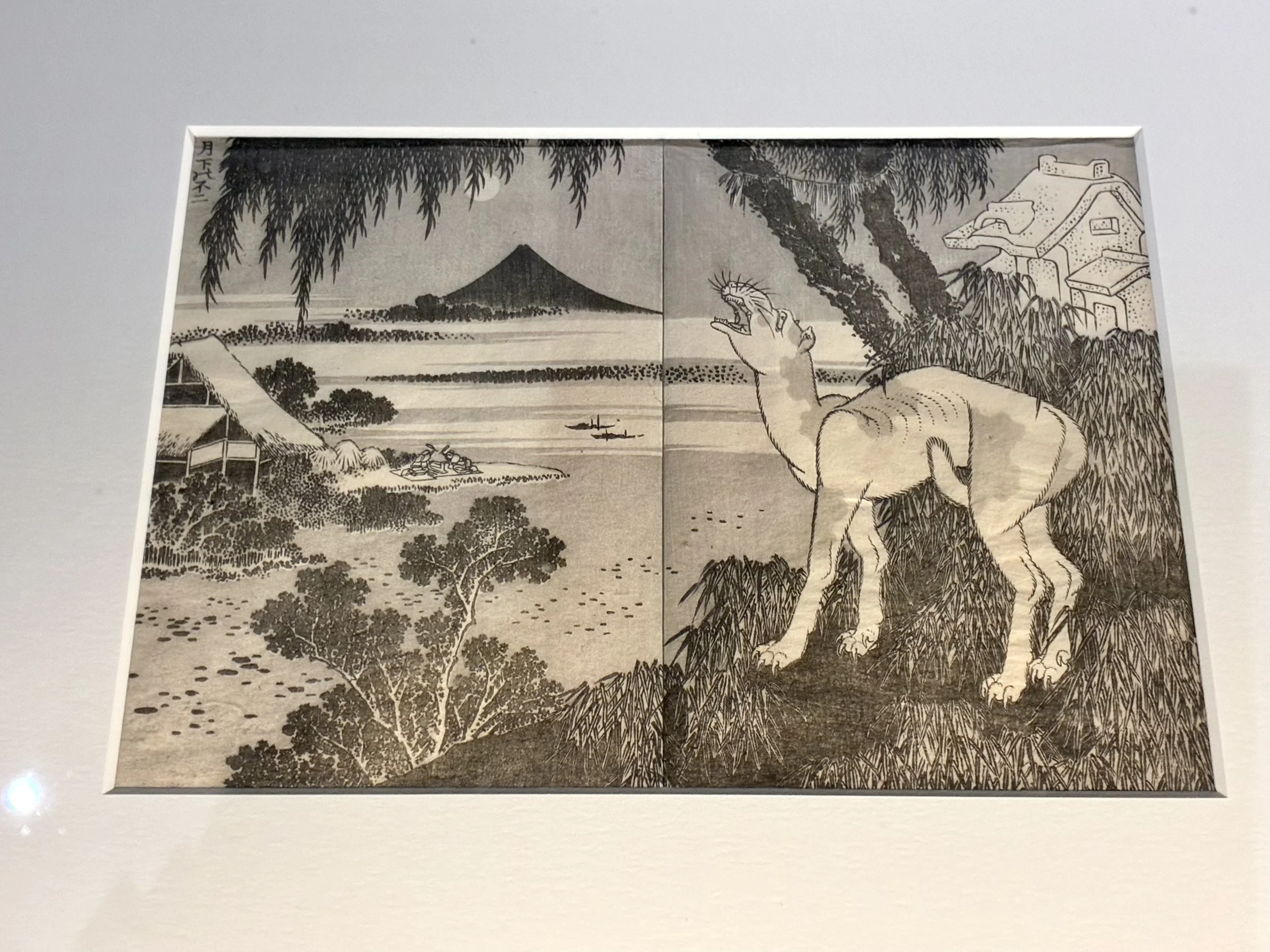

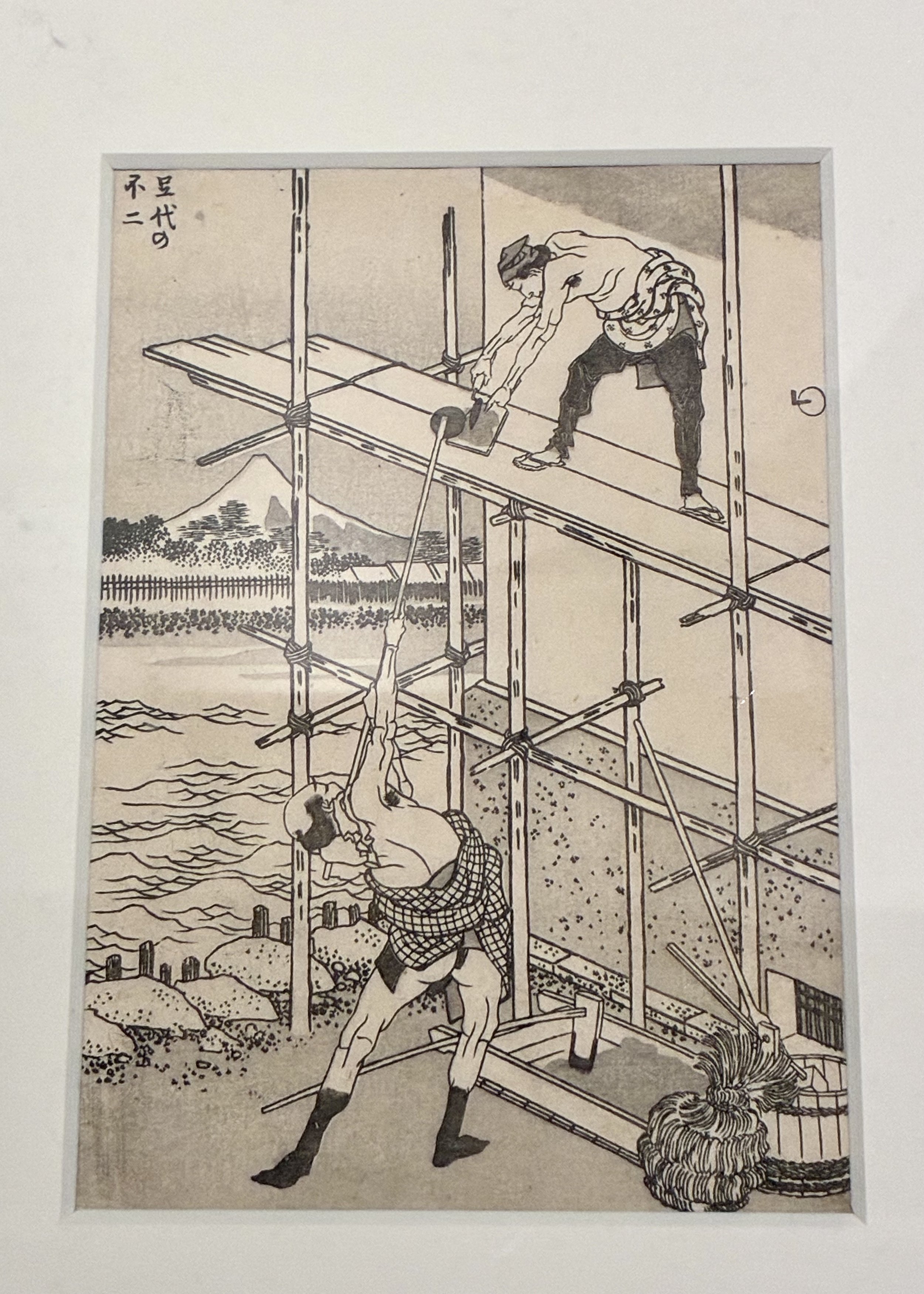

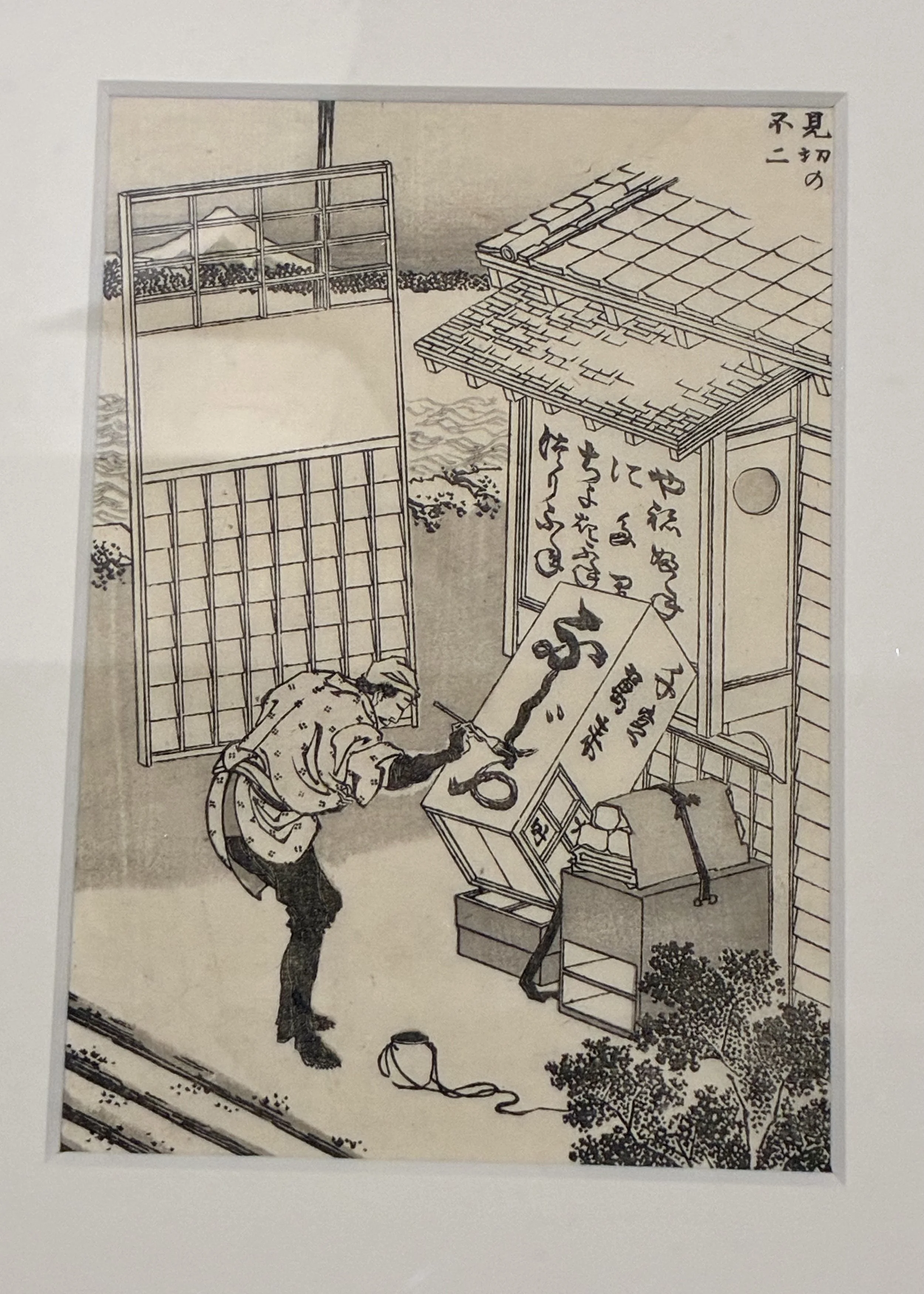

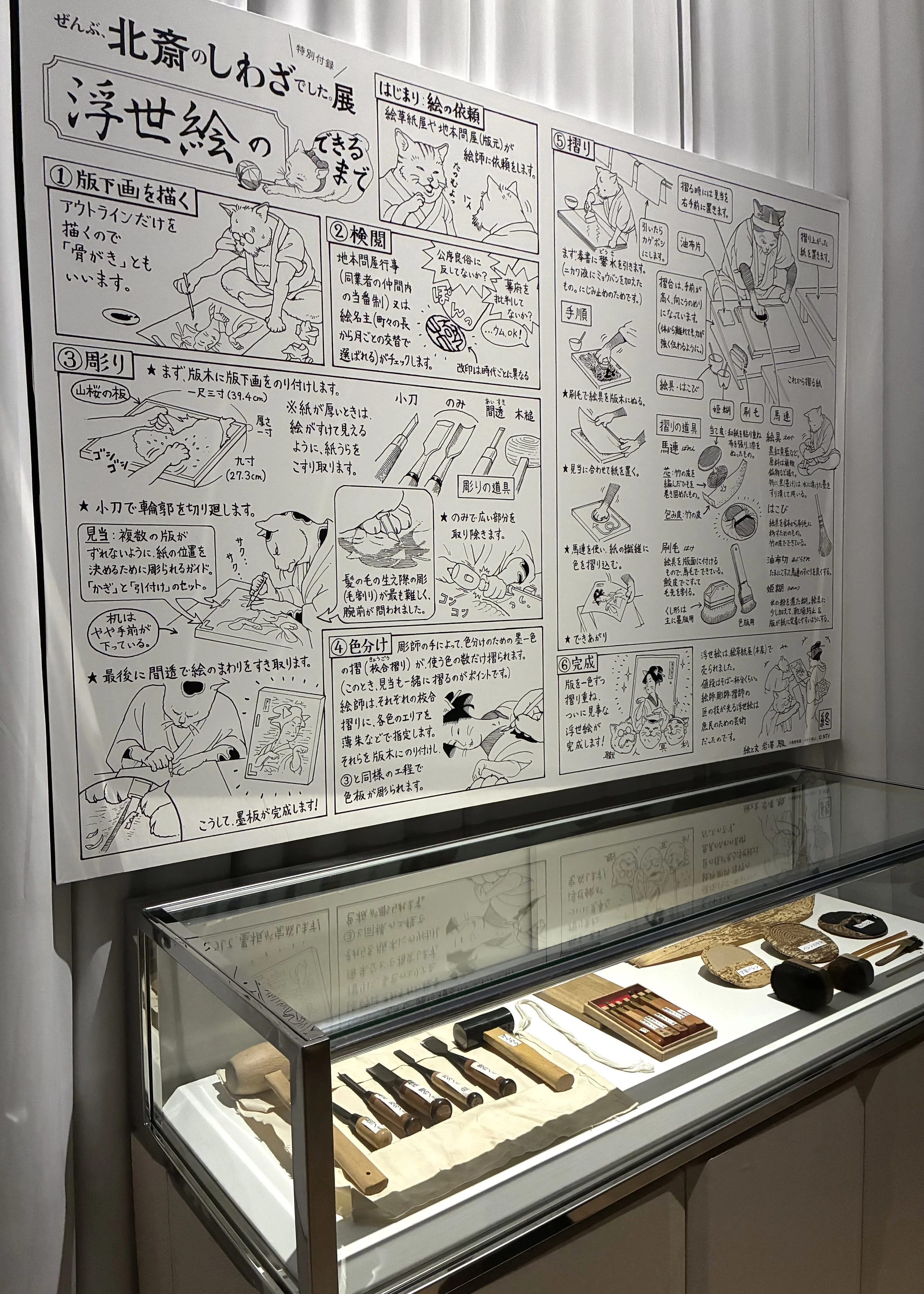

見える/見えない/描く/描けない Visible/Vanishing/Drawn/Unpainting

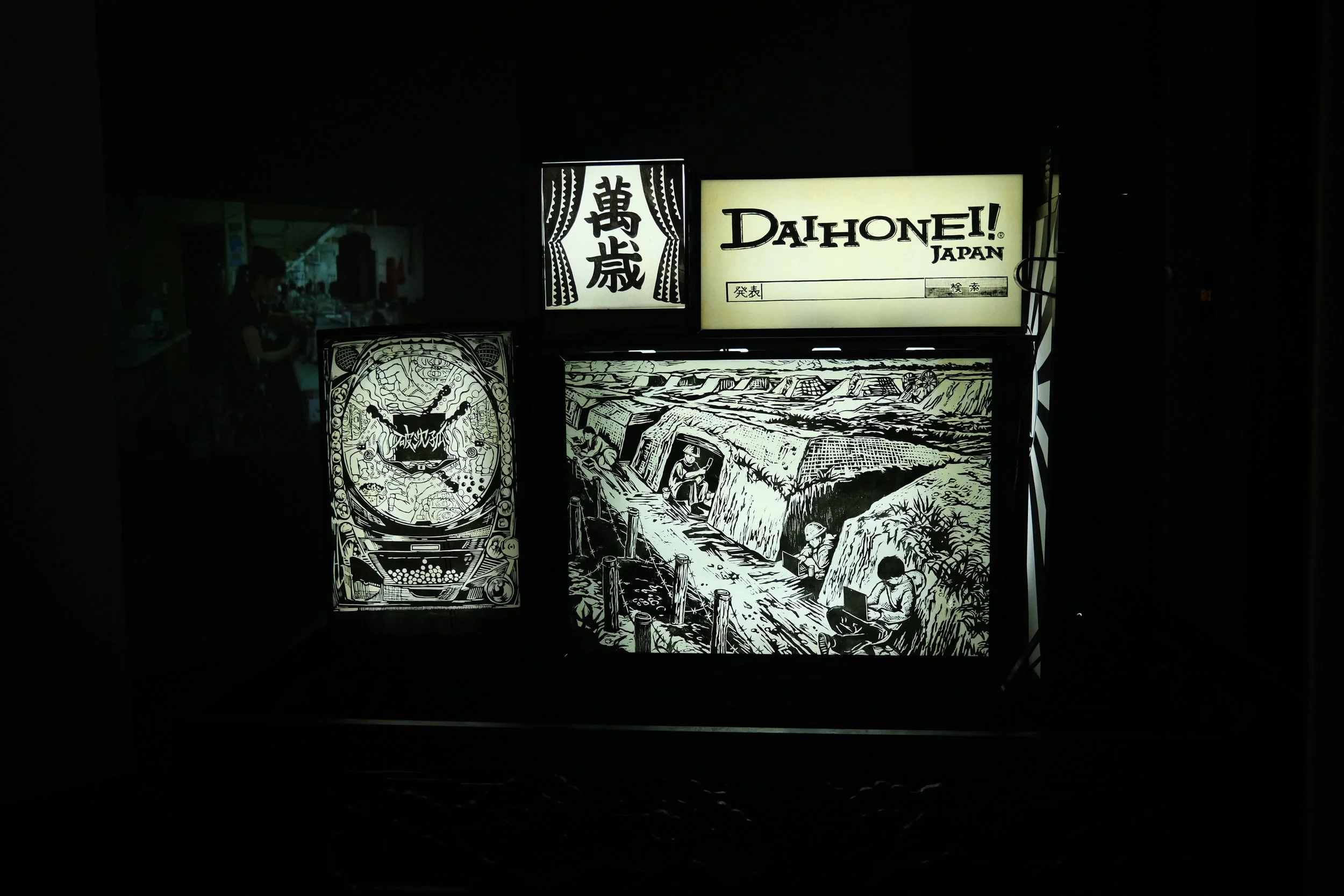

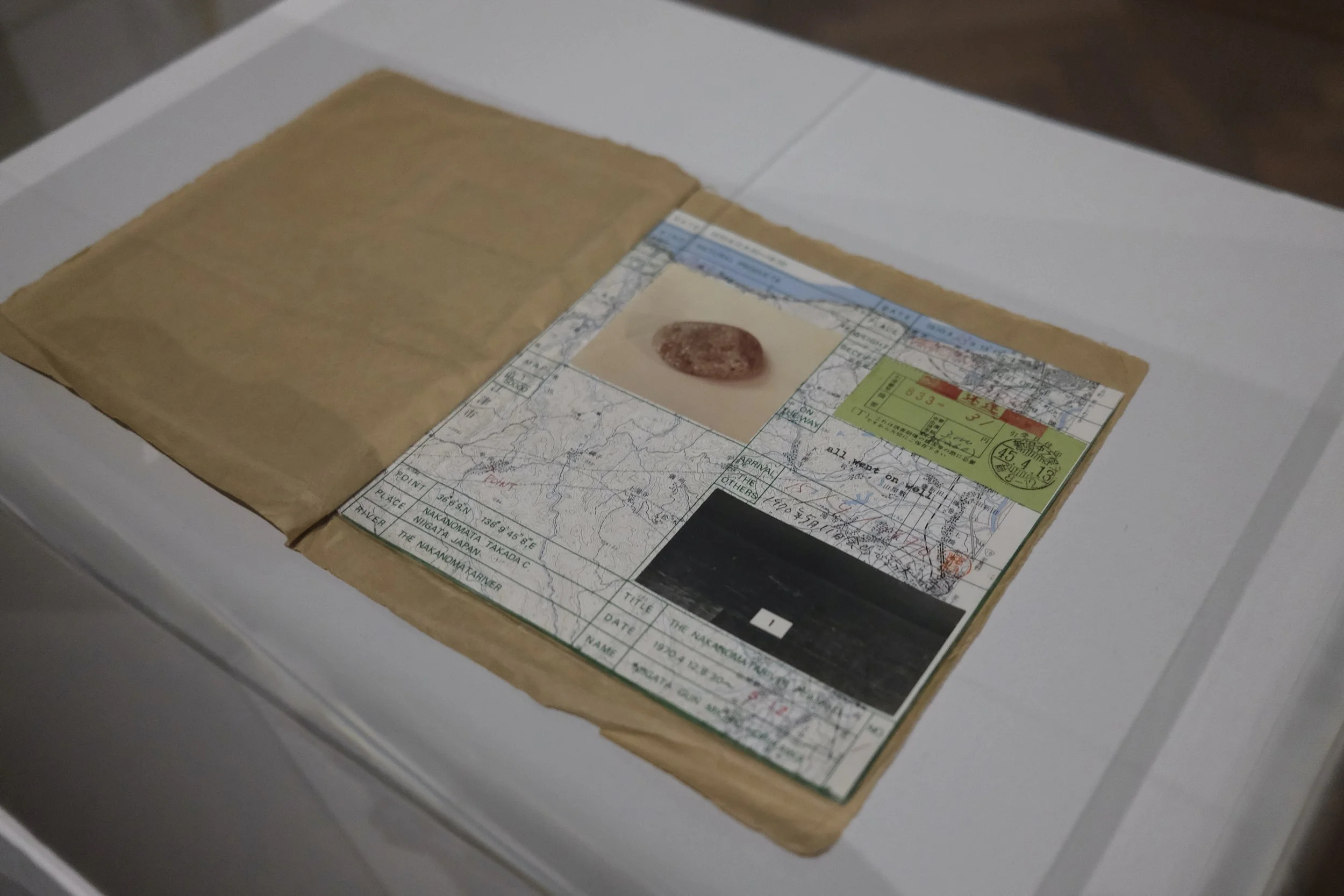

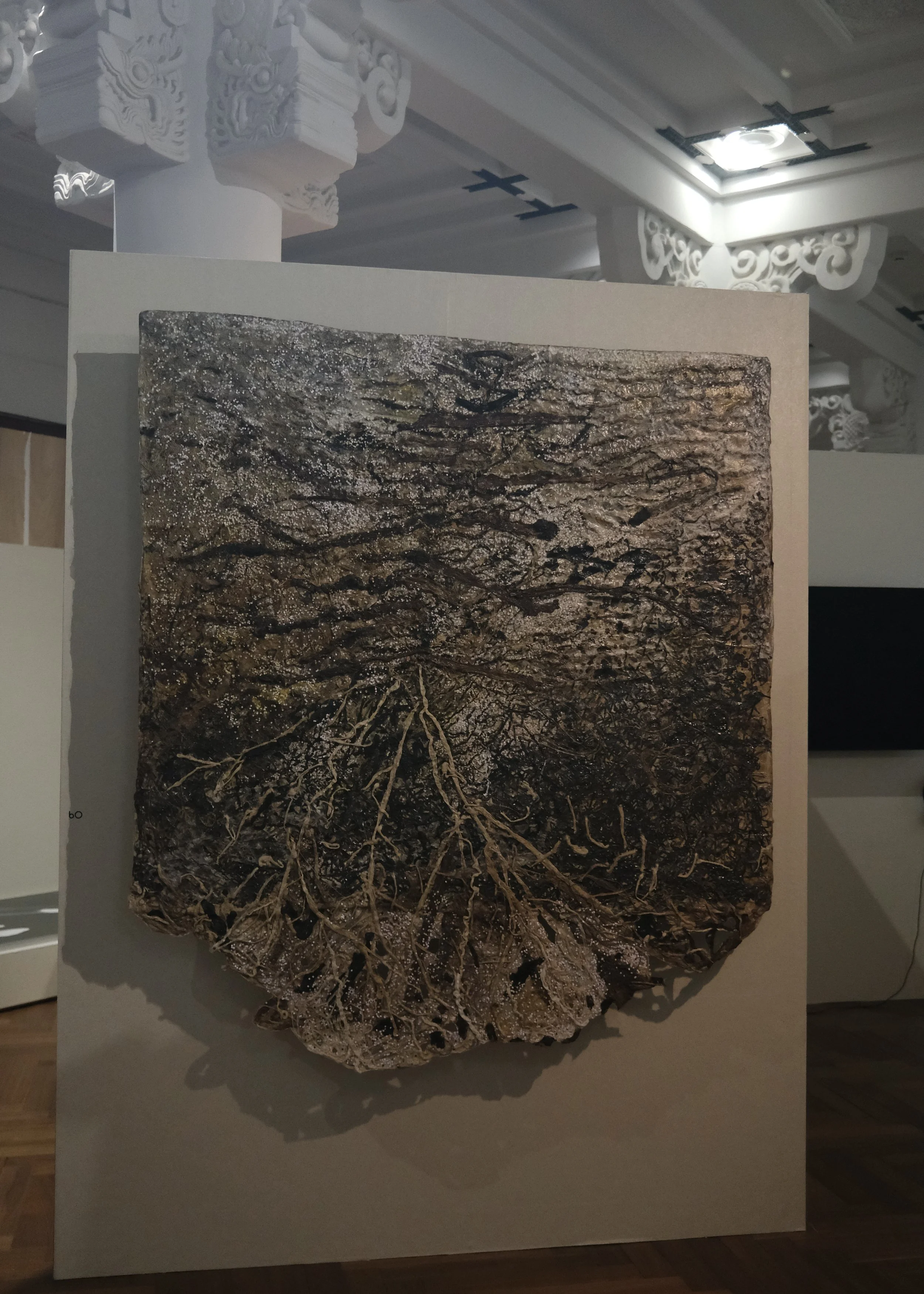

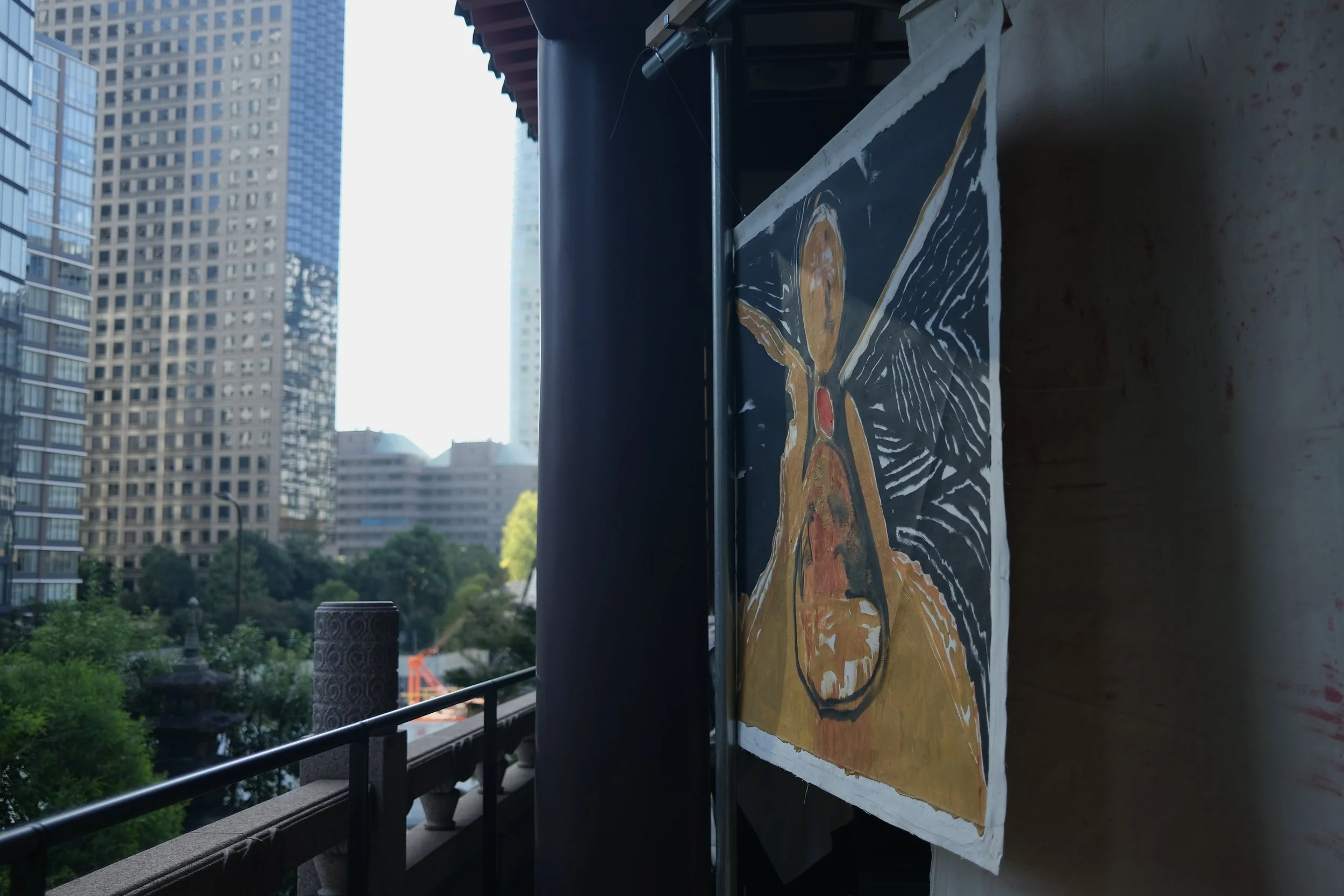

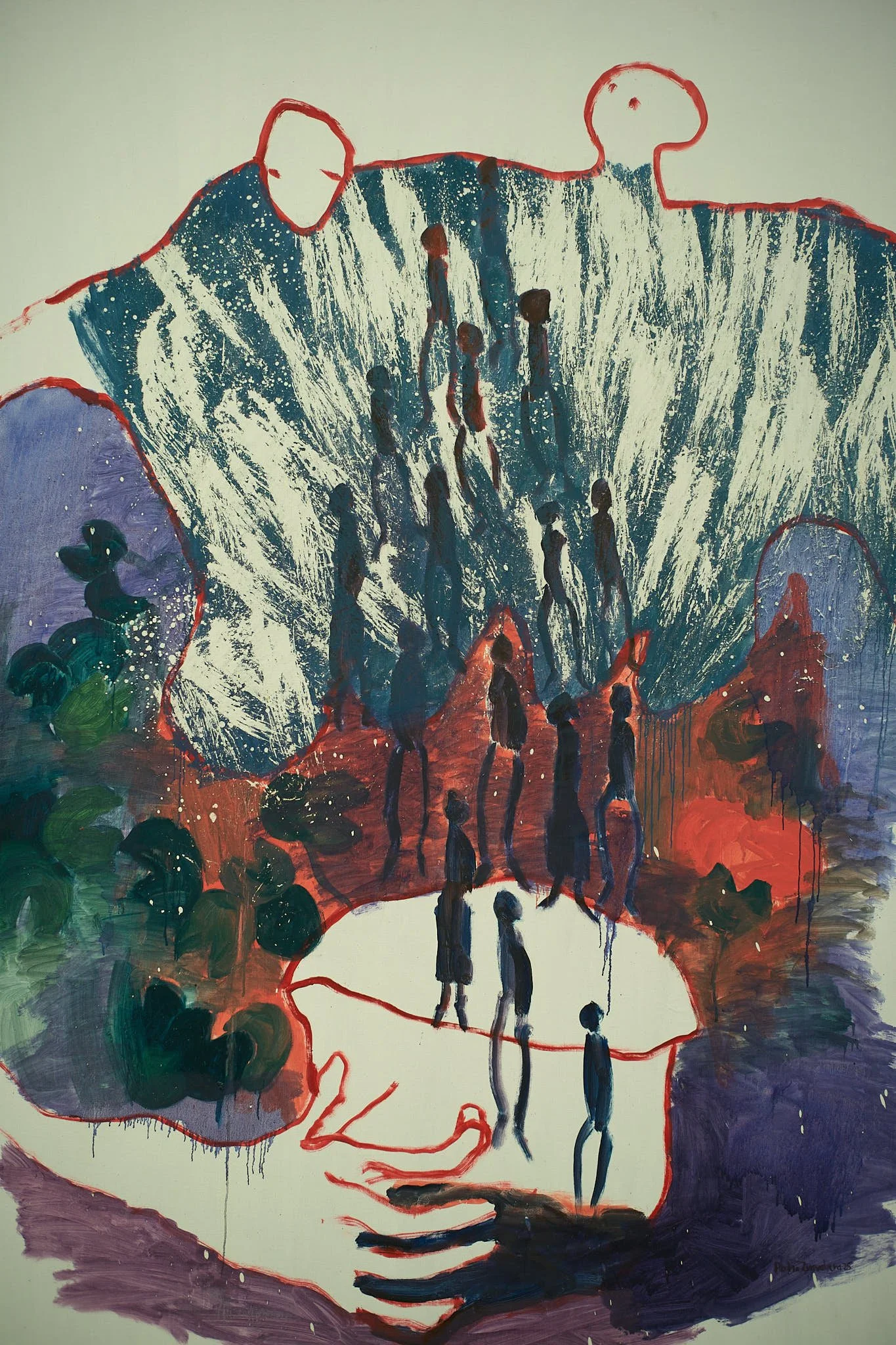

BITIONS Taro Maruyama “Expanded Rooftop and the Vital Energy Map”

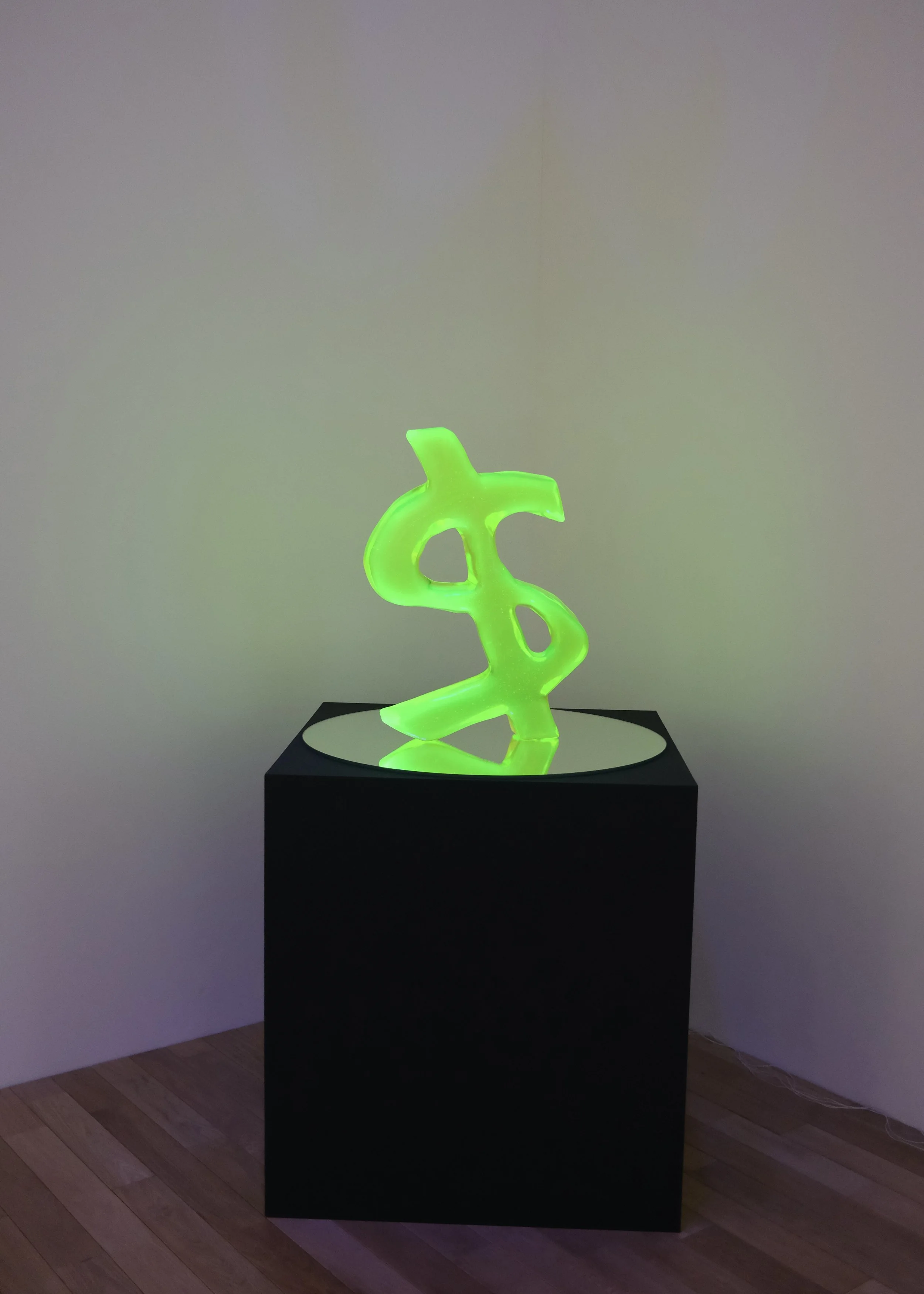

WHAT IS REAL?

Monuments

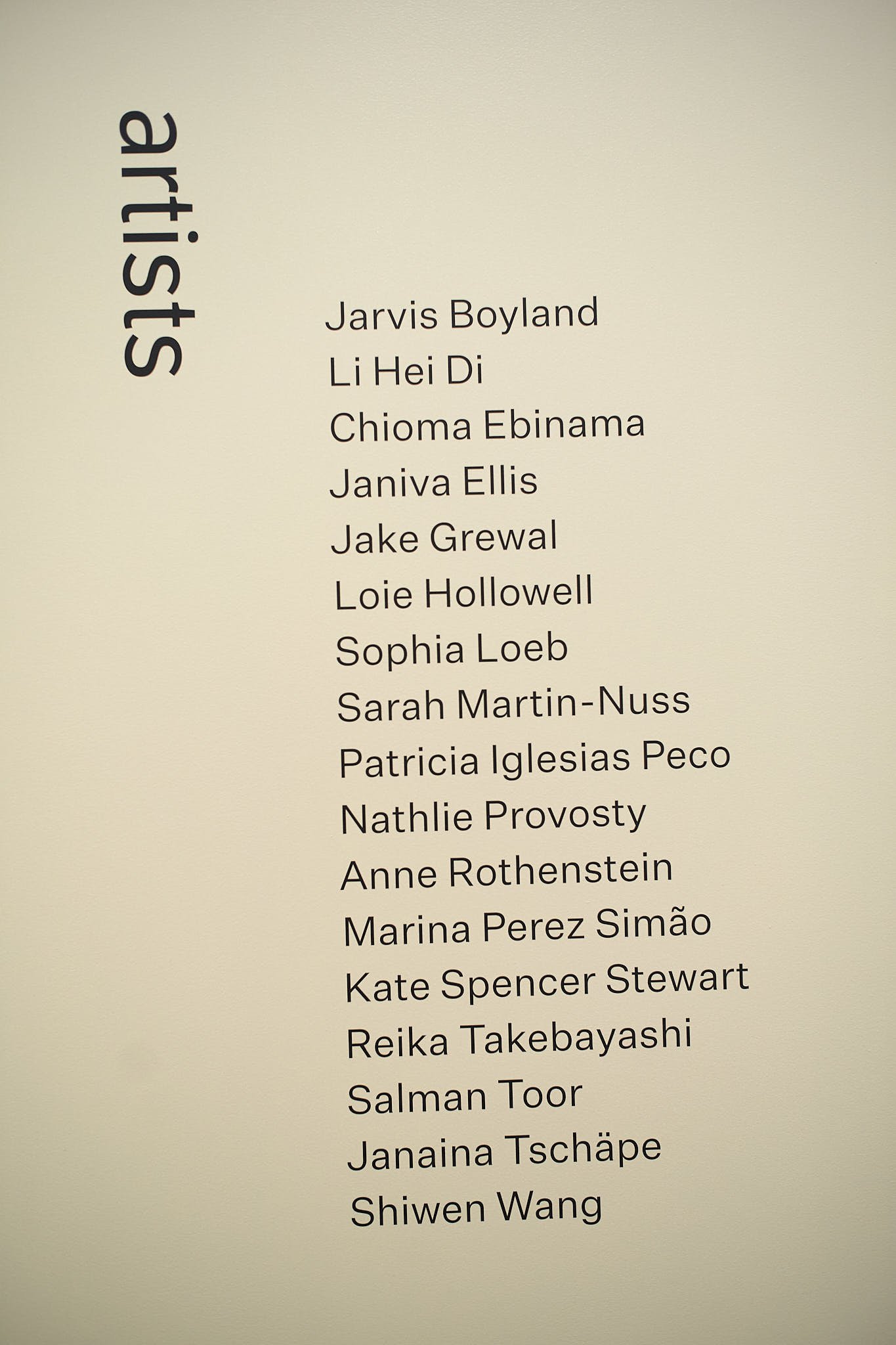

On view Oct 23, 2025 – May 3, 2026

The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA

More Info

MONUMENTS is presented at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA and The Brick (518 North Western Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90004).

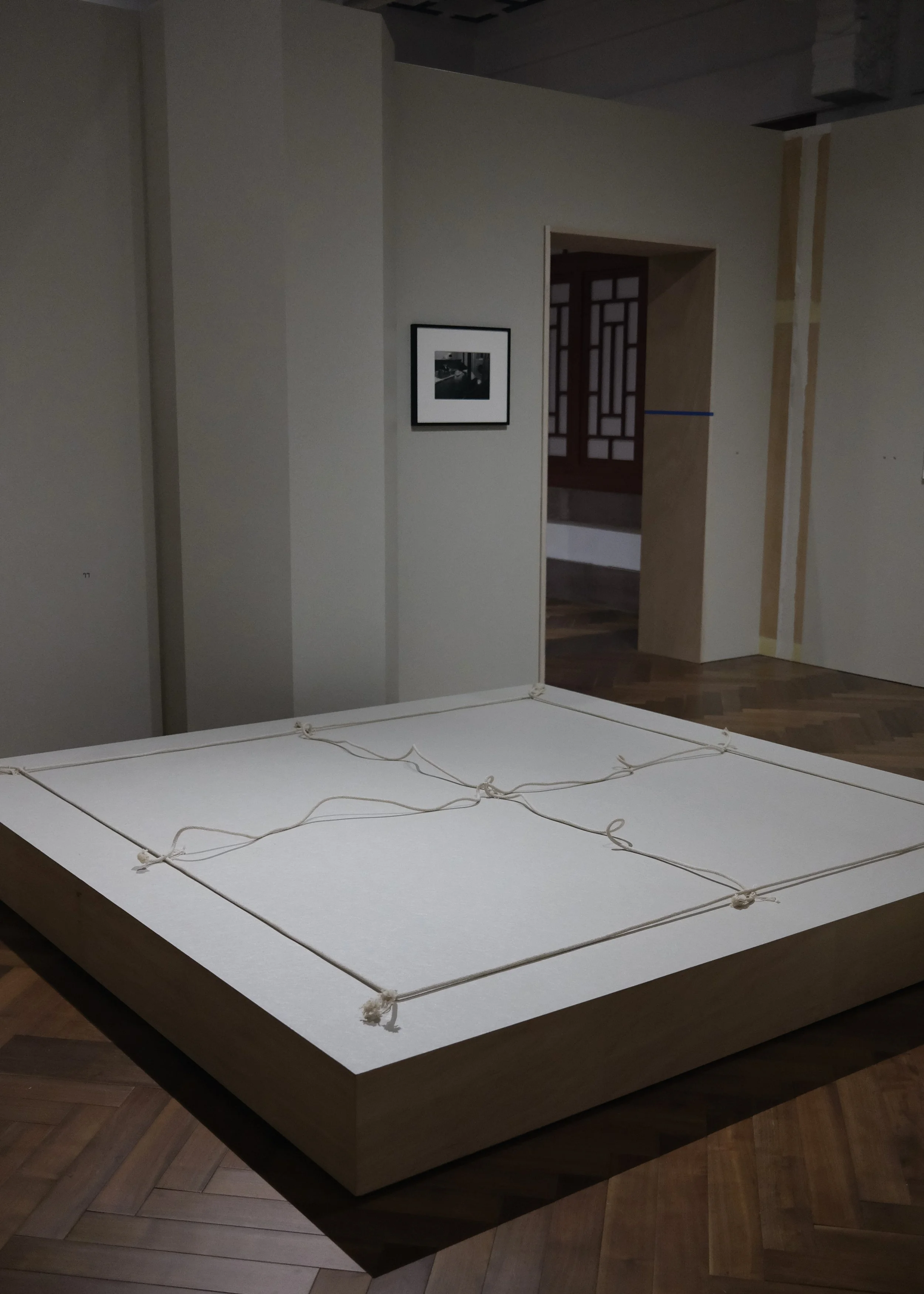

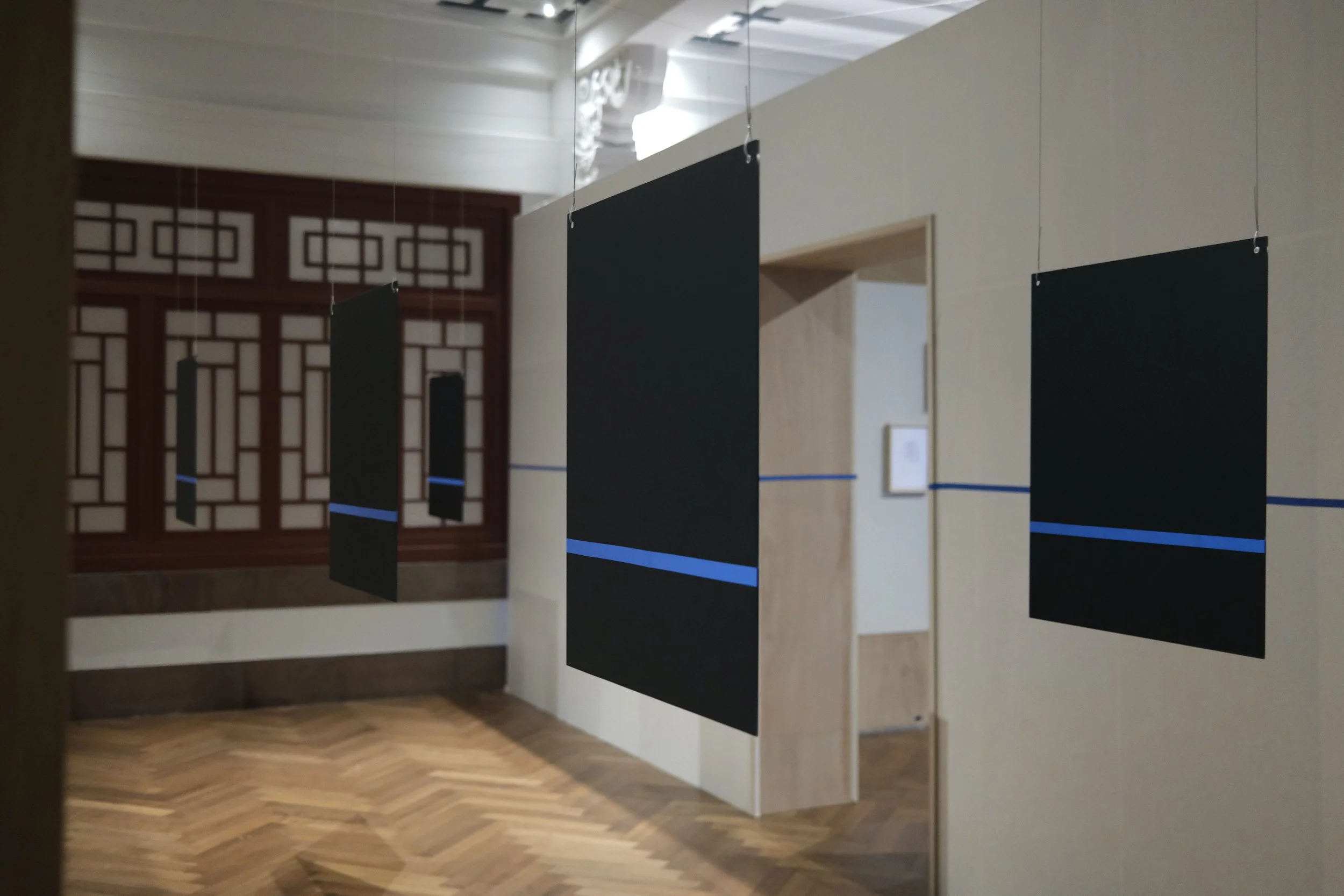

Co-organized and co-presented by MOCA and The Brick, MONUMENTS marks the recent wave of monument removals as a historic moment. The exhibition reflects on the histories and legacies of post-Civil War America as they continue to resonate today, bringing together a selection of decommissioned monuments, many of which are Confederate, with contemporary artworks borrowed and newly created for the occasion. Removed from their original outdoor public context, the monuments in the exhibition will be shown in their varying states of transformation, from unmarred to heavily vandalized.

Co-curated by Hamza Walker, Director of The Brick; Bennett Simpson, Senior Curator at MOCA; and Kara Walker, artist; with Hannah Burstein, Curatorial Associate at The Brick; and Paula Kroll, Assistant Curator at MOCA, MONUMENTS considers the ways public monuments have shaped national identity, historical memory, and current events.

Flora Yukhnovich Bacchanalia

30 October 2025 – 18 January 2026

Hauser & Wirth, Downtown LA