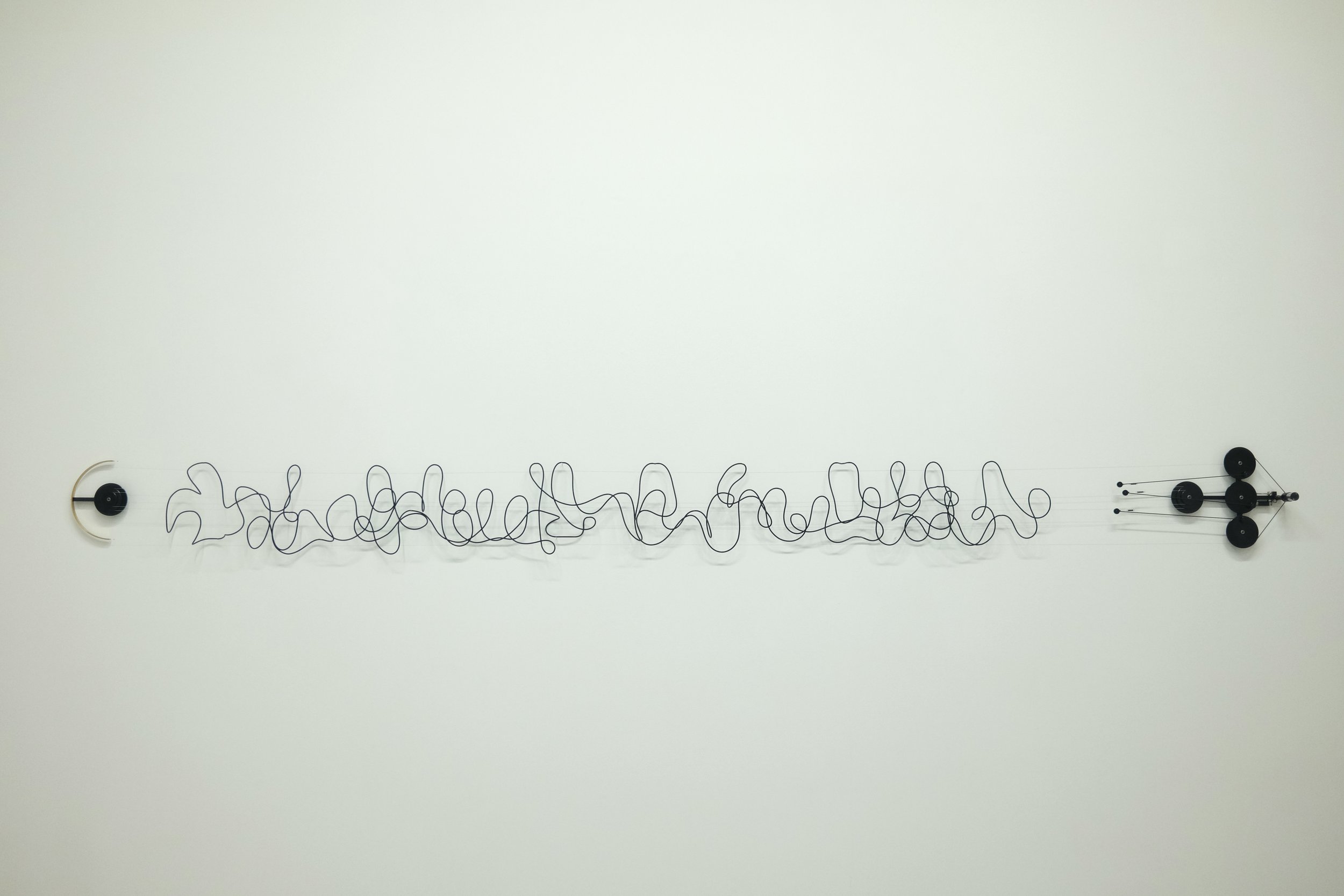

Pe Lang Future Relics

ELYSIUM - a visual history of angelology

At issue with Aquinas's systemization isn't that passages such as the one quoted above don't make sense, but rather that they make too much sense. Serpentine though the reasoning may be, Aquinas's logic is unassailable and, based on the axioms he assumes, conceives of an angelology as rigorous as Euclidian geometry. What's unclear is whether any of it corresponds to an actual reality. With the rise of Scholasticism toward the end of the Middle Ages, what we see in evidence isn't an overabundance of faith but rather a crisis of it. What's clear in reading Aquinas-especially once it's remembered that he abandoned his own philosophy after a mystical experience that was supposedly infinite in its beauty-is that the Summa Theologica is a project of trying to convince yourself of something. Neoplatonists had the benefit of admitting that their systems were forever deferred, always falling short of whatever ultimate things flit unseen beyond the veil of human senses. When it comes to approaching angels, science is deficient in a manner that poetry simply isn't. A powerful tool, poetry — as long as it isn't mistaken for the referent-one that dominated until the High Middle Ages, only to return with the Renaissance humanists, occultists, and Neoplatonists. The Areopagite was among the most subtle of thinkers in this regard, in avoiding intellectual idolatry that confuses the painting of a winged being with intangible celestial forces themselves—a feature of the aforementioned apophatic tradition of which he is an exemplar, a wisdom that understands that the spoken god is never the real God. This is the "being beyond being" as he calls it in Divine Names, something that "is cause of all; / but itself: nothing." What Dionysius's angelology offered was a system of symbol, metaphor, simile, and cipher in which to express the experience of the inexpressible, to hear that which is silent, to see that which is invisible. A language to speak of those without tongues, a hand to write among those lacking limbs, a mind to envision for the thought that is greater than all experience. For Dionysius, angels were both agents of inspiration and a metaphor for meaning; returning celestial beings to their most crucial function, his was a theory of the message. - ED SIMON Elysium page 64

ELYSIUM - a visual history of angelology

Again and again, I return to this question of who among us can see the angels, and why they are so often invisible to the preponderance of people in the contemporary world. In past epochs, visionaries and prophets, mystics and poets were privy to the shimmering resplendence of the celestial choir flitting about in the cosmos. I, who have never seen an angel, and can scarcely believe that such a creature is possible, am envious of William Blake with his espying them in the trees at nightfall, every golden wing quivering in the sunset, every halo glowing in the dusk. As with so much of that which ails us—our nihilism and our prejudices, our alienations and our oppressions-I've long favored that myth of disenchantment, that faith that at one point the ladder to heaven was a bit sturdier and one need not have been as remarkable a soul as Blake to hear the flapping of the angels' wings. "There is a widespread sense of loss here," writes the philosopher Charles Taylor in A Secular Age, "if not always of God, then at least of meaning." I'm not sure that an overabundance of meaning was ever the birthright of humanity, but like all creation myths, this parable about disenchantment does what it needs to do in aiding me to make sense of the world. Because an angel is not something to be etherized and anatomized, dissected and categorized; an angel refers to nothing so vulgar as a body that can be examined with scalpel and calipers, but is closer to a fleeting feeling, a figure of speech, a turn of phrase, a sense that there is something greater and truer and more beautiful than you, and that despite it all you are loved and are capable of loving in return. For you see, an angel is merely love that is given a proper name, grace that is imagined with a face. A blessed wisdom that is so close we can sometimes hear it call to us in our names, the reminder of a wholly foreign and holy Other beautiful and irrational goodness. -ED SIMON Elysium page 15

Julie Mehretu. Ensemble

Oliver Lee Jackson Machines for the Spirit

IVA GUEORGUIEVA Seascapes, Snowscapes, Kukeri

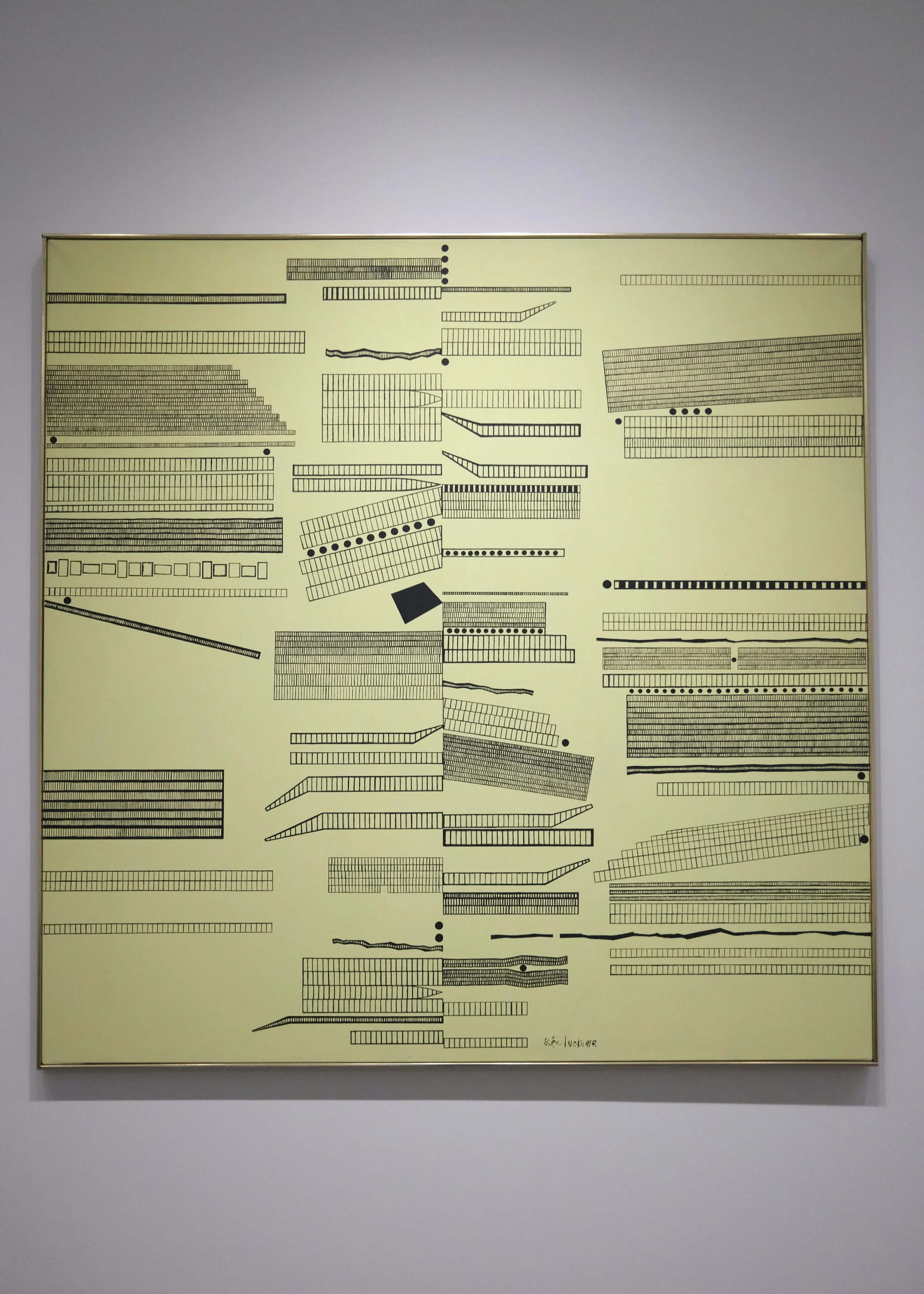

Jongsuk Yoon - Yellow May

Interconnected Landscapes

MATTER(s) - Group Exhibition

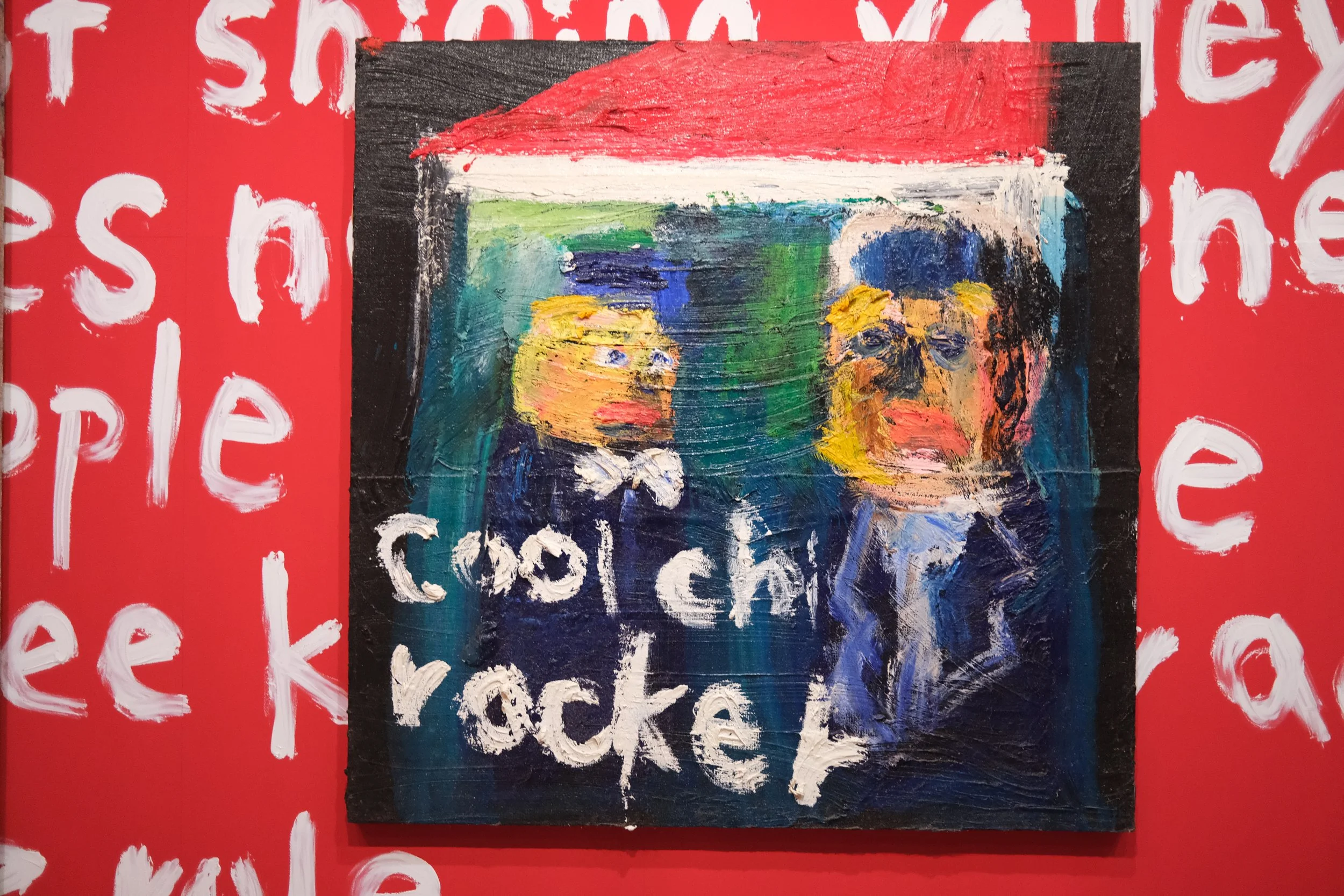

Nana Funo 「このために生まれた」 “Born for This”

Hiroto Tomonaga -望遠 In the distance

水戸部七絵 / Nanae Mitobe - People Have The Power

Artizon Museum - Permanent collection

https://www.artizon.museum/

Tokyo

Brancusi: Carving the Essence

March 30 [Sat] - July 7 [Sun], 2024

Artizon Museum, Tokyo

Rei Nakanishi - 「表層の季節」

GINZA TSUTAYA BOOKS

May 18 - June 5th, 2024

Andy Summers Photography: A SERIES OF GLANCES

Leica Gallery Tokyo

5 April to 7 July 2024.

Installation view of Matthew Barney - SECONDARY: commencement

LOOK INSIDE A New History of Western Art

Ekphrasis page 128

One final concept from Greek antiquity that deserves some explanation here, even though it is not directly related to art theory, is ekphrasis (Exparis or descriptio in Latin) meaning an artful description. Ekphrasis was a standard part of the progymnasmata, the exercises given to students of rhetoric. Would-be orators had to describe a sculpture or painting as vividly and accurately as possible, so that the visual narrative they created would allow their audience to form a clear idea of the work. Theorists of rhetoric were quick to appreciate this ability to 'speak to the imagination'. Ekphrasis had a substantial impact on art in the Renaissance as it enabled the artists of the time to work in the opposite direction. Knowledge of antique art was limited in the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, not only outside Italy but within the birthplace of Renaissance art itself. Barely any trace had survived of paintings from antiquity; all that remained of Zeuxis and Apelles' masterpieces were the beautiful descriptions of Horace and Pliny, and so their texts, along with those of other authors, began to be used in an attempt to reconstruct antique art. The translation from image to word was thus reversed, as words were turned back into images. The so-called Calumny of Apelles - a description of an allegorical composition by the most famous Greek sculptor - is an example as striking as it is well known. The painting was described by Lucian and was drawn and painted by numerous Renaissance masters, including Botticelli, Mantegna, Raphael and Bruegel.

NEW HISTORY OF WESTERN ART

Chapter 2 Art as Idea page 122

Thinking about art has been dominated by the concept of 'mimesis' since antiquity. Freely translated, the ancient Greek term refers to the 'imitation' of nature which human beings sought to recreate in their art until well into the nineteenth century. The degree to which the creator succeeds in this goal has always been one of the most important benchmarks for the quality of the work of art. Successful mimesis resulted in what the Greeks - who did not have a word for visual artworks - called mimemata (singular mimema: the result of imitation). The concept is of the utmost importance to any understanding of Western art history. Mimesis was the focus of Western visual culture from the antique era until the paradigm shift of Impressionism and its offshoots began to undermine the principle from the latter part of the nineteenth century. No artist before then had dared to produce art that did not consider nature its ultimate model. To this day, many people still judge a work's merit in terms of its mimetic qualities. Consequently, the principle of imitation was at the forefront of the artist's possibilities and limitations for centuries. The techniques of oil painting and linear perspective, for instance, did not just develop out of nowhere but were vital steps in the ancient quest for perfection in the emulation of reality that has typified Western art. Even more than that, the notion that art is essentially an imitation of nature actually fed through over time into the visual culture of non-Western religions and cultures. The ancient Greek concept played an active part, for instance, in the visualisation of Buddhism, whose founder was represented symbolically during the religion's first centuries (up to the fourth century BCE). It was only after Alexander the Great's conquests in the Indus Valley that the Buddha began to be depicted as the idealised human figure we know today [2.6]. Mimesis might thus appear simple and self-evident at first sight, yet it is far from being so. Simulating what we see is not a straightforward process. The term itself is not unambiguous either and has undergone various shifts in meaning since ancient times. Over the centuries, mimesis became an umbrella concept taking in ideas such as imitation, representation, similitudo, simulacrum and prototypum. If we delve more deeply into the phenomenon, which is precisely what occurred in antique Greek culture, emulation proves to be highly complex. Artists can, for instance, imitate nature in an idealised way by seeking to perfect it, but they can also strive for a 'photographic' realism [2.7, 2.8] or give free rein to their creativity and imagine things that cannot be imitated, as they do not actually exist. The centaurs on the famous Parthenon frieze [2.9 ] appear lifelike, but these hybrid mythological beings - half human, half horse - are obviously a product of human imagination.